Ten Supply Chain Risk Mitigation Strategies in Pharma

In our second piece looking at tackling drug shortages, we examine common supplier risk mitigation strategies.

The sources of pharma supply chain risk are varied and ever-changing. As we discussed recently, disruptions can result from anything from conflict to climate change. In most cases, businesses can do little to address the cause; they can only mitigate the consequences.

Partly because of the range of risks, strategies to mitigate them are just as diverse. But it’s not simply the variety of potential causes requiring different responses. It is, first, that in many cases no single strategy can deliver the resilience required; and, second, that, organisations facing the same event, can see very different disruptions to their business. The vulnerabilities of each supply chain and the potential impact of interruptions are unique.

Given the range of risks and difficulty calculating the probability of disruptions, it is the impact – the real-world value at risk – that must determine the appropriate response, both in terms of the nature and extent of mitigation efforts. Here, then, are ten to consider.

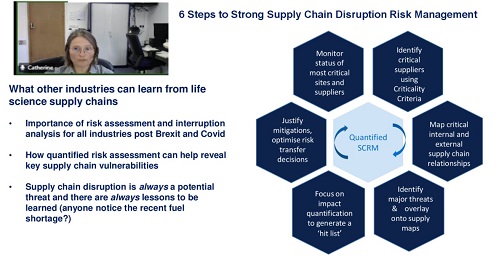

1. Map and assess

This is not so much a mitigation measure as the foundation on which all mitigation must be based. Just as you cannot manage what you can’t measure, you cannot mitigate what you can’t map.

Improving transparency in the supply chain can quickly reveal potential vulnerabilities. Crucially, it can also show where there are concentrations of risk, with dependencies on multiple suppliers concentrated in a particular region, for example. Governments increasingly recognise the importance of transparency, too, as is reflected in legislative proposals such as the MAPS (Mapping America’s Pharmaceutical Supply) Act in the US and increasing discussion in the UK and Europe.

Regardless of regulatory pressure, however, visibility of the supply chain is the prerequisite for effective risk management. And it is eminently achievable with solutions such as SCAIR® available to help map suppliers and identify dependencies and choke points.

2. Monitor

The work is never done. Risk mitigation is an ongoing process and requires continual monitoring. There are multiple moving parts.

First, changes in the supply chain naturally occur as businesses go bust or merge and new threats, risks and vulnerabilities evolve. Supply chain maps and plans must remain current. Second, in a crisis, early warning and detection of disruption can significantly enhance responses, enabling businesses to secure alternative suppliers or services to restore production before those suppliers are overwhelmed by demand from competitors.

Again, supply chain monitoring is not a mitigation measure in itself but supports timely and appropriate action to prevent and alleviate disruptions.

And, again, SCAIR® makes this possible by, for instance, interfacing with Location Risk Intelligence, reinsurer Munich Re’s solution for assessing risks from natural hazards and climate change. It enables users to identify in near real-time where natural disasters impact their supply chain and benefit from robust, location-specific climate change predictions to help direct forward-looking investments in mitigation.

3. Broadening the supply base: The more the merrier

When moving from monitoring to mitigation measures, increasing the number of suppliers for critical ingredients or products is among the most obvious strategies. If one source is disrupted, they can simply turn to another. But it is, of course, not so simple, and the complications underline the importance of the previous steps.

First, the ability to map the supply chain and bring true transparency to its vulnerabilities will enable businesses to avoid the illusion of diversity: Where alternative suppliers do little to boost resilience because they are exposed to the same risks of disruption as existing suppliers. That is most likely to occur where the new business is located in the same region as existing suppliers and subject to the same weather, regulatory and geopolitical risks.

Second, even with alternative suppliers in place, a rapid response to disruptions can be essential to secure increased orders if a disruption also affects competitors’ supplies. Monitoring enables this.

Finally, the process of finding, validating and approving a new supplier can be time-consuming and costly. Consequently, as with all mitigation measures, it is important to prioritise the critical (but not necessarily costly) supplies essential for high-value products.

4. Quality and quantity: Removing the weak links

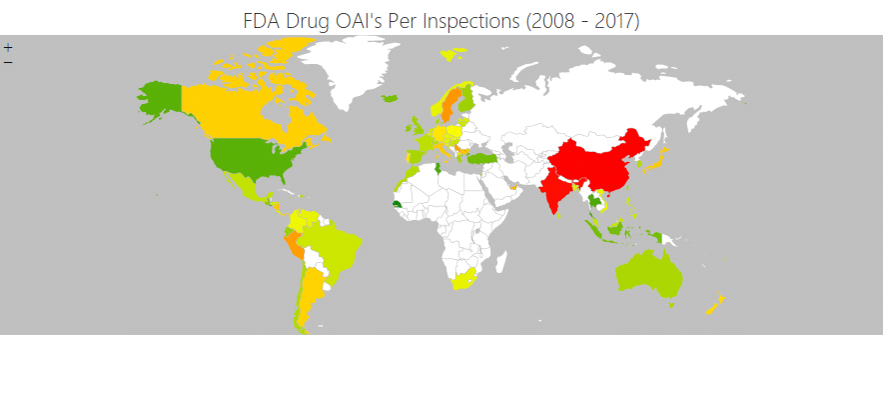

Expanding the supply base can improve resilience, but so can cutting out the dead wood. Improved visibility of the supply chain enables businesses to identify recurring issues with suppliers and more closely scrutinise their critical supplies for high-value products.

Where that scrutiny or repeated problems provide cause for concern, businesses can act to not simply identify potential alternative sources but replace unreliable suppliers with these. Again, a value-at-risk approach will inform them where the expense and trouble of doing so is justified.

5. Safety and buffer stock

Sometimes, just in time just isn’t enough. As we explored last month, the rise of just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing has always been, at best, a mixed blessing for pharma. A strategy to cut working capital developed in automotive businesses where suppliers and the assembly plants were relatively close is arguably less suitable for Western pharma businesses relying on China and India for their active ingredients.

Furthermore, as already noted, switching to alternative suppliers may be relatively simple for some manufacturers. In life sciences, by contrast, regulatory and safety issues can require lengthy qualification and process revalidations.

The accounting and business benefits of JIT mean its principles will always have an influence in pharma. Storage costs, particularly for supplies requiring careful control of temperature and humidity, are not negligible. In some cases, long-term storage is not even practical. Nevertheless, where it is, and where the value of end goods supports it, maintaining an extra stock of critical supplies remains a crucial bulwark against disruption.

6. Nearshoring

An obvious answer to some of the challenges of just-in-time production is to bring production closer to home. It’s been an essential element of government thoughts on boosting the resilience of critical drug supplies since the pandemic. Expanding onshore and nearshore production was among the strategies proposed early in the Biden presidency in its 100-day supply chain review report in 2021.

It might be an obvious answer, but it’s not a simple one. There is a reason that about 80% of active pharmaceutical ingredients are produced abroad in countries such as China and India: Cost. As we’ve discussed before, the case for onshoring is complicated by the costs of setting up and running domestic production facilities, particularly for low-margin, generic drugs.

Moreover, while one key public policy priority is ensuring the continuous supply of critical drugs, another is controlling their costs. Those two priorities can conflict.

7. Insurance: Cover for the unavoidable

Not all disruptions can be successfully mitigated. Losses occur, and that should be where insurance steps in.

In this respect, SCAIR®’s exposure assessment and Natural Catastrophe Monitor tools have a double use. First, they enable businesses to assess the potential impact of catastrophic events and respond more rapidly and effectively where they occur, potentially limiting losses. Second, they provide location-specific visibility of exposures and the value at risk to help simplify the task of calculating insurance coverage requirements.

The importance of such tools is likely to grow as the effects of climate change (already being felt in rising losses from “secondary perils”) grow. Here tools such as Location Risk Intelligence can help businesses not just ensure they have adequate business interruption cover today, but also plan for the future by showing how climate change could affect their critical suppliers in years to come.

8. Compliance strategies

Increasing risks from climate change have prompted regulatory requirements for large businesses to report risks to their supply chains from extreme weather. For many, this reporting is likely to be fairly basic – estimating losses from revenue dependency, for example, and using historical data for locations to assess risks (failing to account for the changing climate).

The tools mentioned above, however, provide an opportunity to make this more than a box-ticking exercise. Instead, it can be an exercise that brings value and true insight for risk mitigation efforts. With SCAIR®, users can assess contemporary climate threats, factors in mitigating actions, and calculate a robust value-at-risk assessment.

Since businesses have to do the exercise anyway, they may as well make it count.

9. Reducing dependencies

This entry is perhaps a bit of a cheat, because reducing dependencies is the heart of some of the steps above, such as expanding the supply base and removing weak links.

However, a benefit of the compliance process outlined above is that it enables firms to draw up a list of their most vulnerable manufacturing locations, taking account of the concentration of risk in locations – according to the value-at-risk.

With that information, they can examine solutions to reduce dependencies on these suppliers. That may be through diversifying or finding alternative suppliers, changing ingredients, or even diversifying their business and building up alternative revenue streams where the risks to a product’s supply can’t be sufficiently mitigated.

10. Due Diligence

Finally, it’s vital to remember that supply chain risk management is a dynamic process. Company events and the passage of time can introduce new risks. Mergers and acquisitions are just among the most visible and increasingly frequent examples.

Due diligence is vital to avoid issues, particularly when it comes to the regulatory risks that are so frequently behind supply disruptions in pharma. Failure to recognise and address legacy issues from acquisitions can lead to problems dragging on for years. As with so much when it comes to supply chain risk in life sciences, a stitch in time saves nine.