The Usual Suspects: HRT Treatments, ADHD Drugs and Antibiotics are Again in Short Supply. Here’s Why

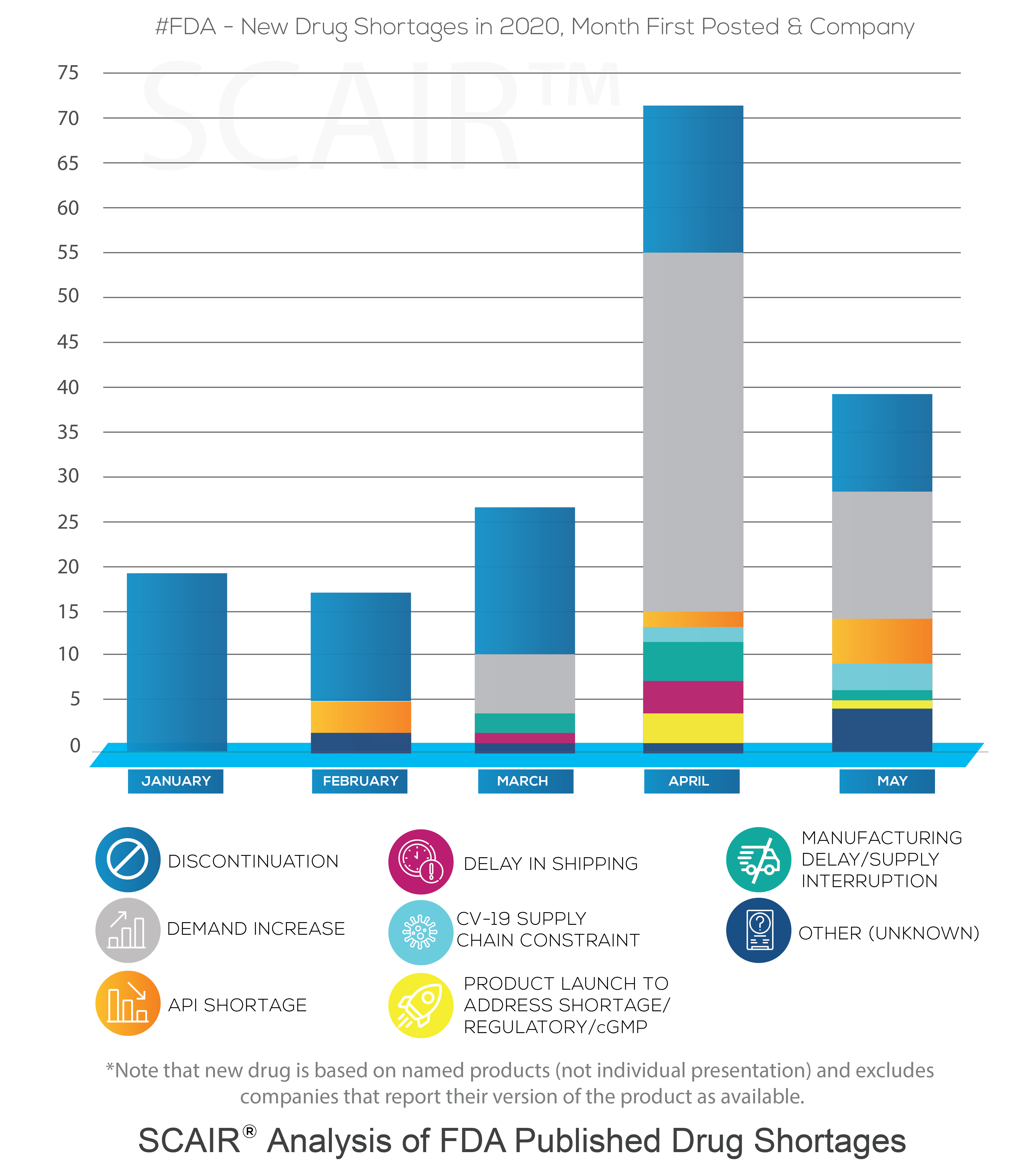

SCAIR® Director of Risk Management Catherine Geyman analyses current critical drug shortages alongside earlier incidents – and highlights some common themes.

The British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA) has published data showing just how serious drug shortages are in the UK right now. These shortages are nothing new, but the scale of the problem is.

The drugs concerned are the usual suspects – they include antibiotics, HRT treatments and medications for epilepsy and ADHD. The two main causes are also familiar – supply chain disruptions and unpredictable demand. This is exacerbated by their underlying lack of profitability, something that makes many generic drugs unattractive to manufacture.

According to the BGMA, there were 101 supply shortfalls recorded in April 2024 compared with 45 in November 2021. The National Pharmacy Association is now urging politicians to make tackling drug shortages a manifesto pledge, in response to the increasing number of Serious Shortage Protocols issued in 2024. This follows a UK Parliamentary Research Briefing published in May 2024, which calls for reform of medicines shortage management.

Hello Again, HRT and Antibiotics Scarcity

The spectre of unobtainable HRT medication has been looming over many women for years. It was an acute problem back in 2022, when the doubling of HRT prescriptions since 2017 was recognised. The demand and supply issues have only continued to increase since then, with little respite.

The Parliamentary Review acknowledges that the history of the HRT shortage problem stretches back to 2018, when oestrogen patches were in short supply. This situation continued into 2019 and 2020. However, a study of FDA Enforcement Reports, performed by Intersys back in 2018 during the ReMedies project, suggested that this was not a new problem: the estrogenic steroid Estradiol was identified as the most frequently recalled drug in the US over the preceding five years.

The acute antibiotic situation in the winter of 2022-23 was another ‘perfect storm’ example of a peak in demand coinciding with manufacturing problems. In December 2022, oral antibiotics such as amoxicillin were in short supply in the US owing to a rise in respiratory infections, especially in children.

In January 2023, the European Medicines Authority also listed both amoxicillin and amoxicillin/clavulanic acid on their shortage list, citing the main issues as a surge in infections coinciding with manufacturing issues and production delays caused by lack of personnel. At a similar time in the UK, the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) issued a series of SSPs for Phenoxymethylpenicillin V (Pen V).

Again, nothing new here. In a 2018 white paper, the Access to Medicines Foundations warned that antibiotic supply chains were close to collapse. A key conclusion was that ‘success will depend on the development of stronger incentives for pharmaceutical companies to enter and stay in the market.’ Sound familiar?

An ADHD Medication Shortage. But Why?

The spotlight, from a drug shortages point of view, is also shining bright on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) treatments. In fact, the scarcity of ADHD drugs was also cited as a case study in the aforementioned Parliamentary review.

Diagnosis of ADHD has rocketed in recent years. In the US, the National Health Interview Survey estimated the prevalence in children to be around six per cent in the 1990s. By 2016, it had risen to ten per cent. As a piece in the New Scientist has noted, it looks likely to have continued rising since: figures from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show ADHD diagnosed in two per cent of children aged three to five years, ten per cent among those six to 11, and 13 per cent for those in the 12 to 17 age group.

And, while it may be much more widely diagnosed in the US, the trend is the same elsewhere. In the UK, 1.4 per cent of boys aged 10-16 had an ADHD diagnosis in 2000. By 2018, that had risen to 3.5 per cent. More widely, a study last year by researchers at University College London, who reviewed seven million individuals on the UK’s IQVIA Medical Research Data, found a 20-fold increase in ADHD diagnoses between 2000 and 2018.

ADHD Medication Shortages: Highlighting the Constraint on Supply Chains

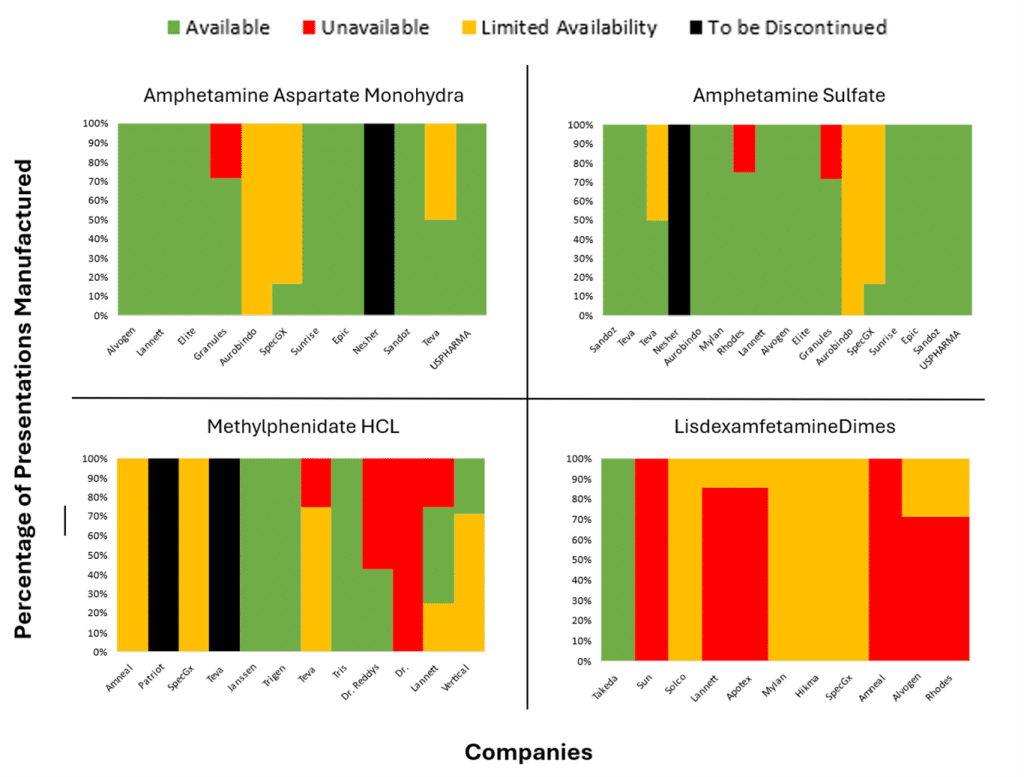

Part of our ability to track the rise in ADHD is from prescription data. Unlike other fairly common conditions affecting childhood learning, for instance dyslexia, ADHD is often treated with drugs. In the UK, five types of medicine are licensed for ADHD treatment: methylphenidate, lisdexamfetamine, dexamfetamine, atomoxetine and guanfacine.

That’s led to suspicions that it’s the pharma industry as much as concerned families pushing the growth in diagnosis. The rise in social media and self-diagnosis has also contributed. Others, though, suspect there’s still under-diagnosis, particularly in adults; and some blame the lack of specialists to diagnose the condition in school children.

What is beyond dispute is that drug supplies are struggling to keep up and that the ADHD medication shortage is the result.

Moreover, Takeda’s dominance of the ADHD market (never absolute anyway) has been dented by the expiration of its patents last February, so in theory the supply situation should have improved with the advent of generic alternatives. Takeda did manage to get a paediatric extension until Aug 2023, but we are now more than six months on from that.

So why was there such an acute ADHD medication shortage in the last six months? Well, in addition to demand spiralling, patient advocacy groups cited the regulatory quota system as the root cause. This explains why multiple companies were impacted: the active ingredients are controlled substances and as such there are centrally imposed limits on how much can be made.

Regulatory Wrangles: Enter the FDA and DEA

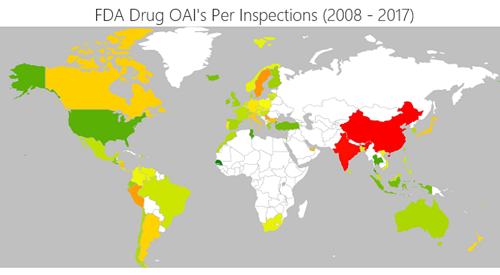

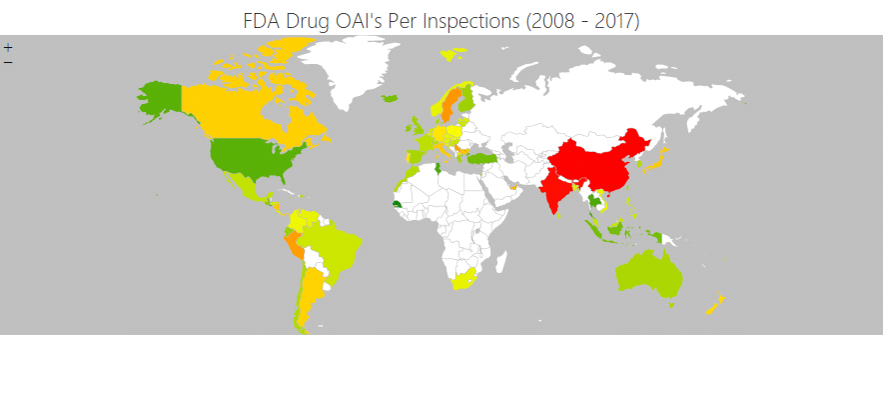

For years, we’ve recognised that regulatory issues and enforcement action are often drivers of drug shortages. It’s a key risk in M&A due diligence, for example, and one reason our Regulatory Incident Monitor is so useful. We also know generics are no panacea. Generics bring down drug prices, widening access. But they do so by reducing manufacturers’ margins, cutting the drug’s profitability. As we’ve previously noted, there’s a price for low-cost drugs.

The ADHD medication shortage adds a new wrinkle to the old story, however. Crucially, this time, it’s not the FDA being blamed for restricting supply but the Drug Enforcement Agency, the federal law enforcement agency tasked with combating illicit drug trafficking and distribution. Crucially, its role includes combating the abuse of prescription drugs. Such drugs include lisdexamfetamine and other potentially addictive amphetamines used for ADHD and classed as Schedule II controlled substances by the DEA.

The DEA denies the claim that they are at the root of the ADHD medication shortage issue. In an open letter last November, DEA administrator Anne Milgram said drug makers were failing to use existing allowances.

However, other DEA regulatory actions have compounded the problem. Across October and September last year, the DEA issued five Orders to Show Cause and one Immediate Suspension Order against six DEA-registered companies. One of the companies to receive an Order to Show Cause was Ascent Pharmaceuticals, which manufactures methylphenidate, a common ADHD drug. Although an Order to Show Cause does not immediately stop production, the company’s need to make changes to comply with audit findings will inevitably impact supply.

Is the Situation Improving?

The quota issue is being addressed by the Drug Enforcement Administration, but the benefits of that decision will take time to filter through.

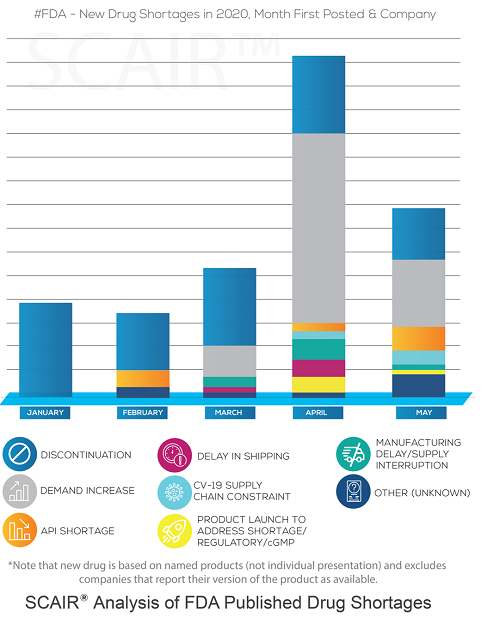

Our own analysis of US FDA Drug Shortages from April and May (see chart showing the % of ADHD presentations that are either completely unavailable, supply constrained, to be discontinued or available), backs up the claim that the situation is improving; there are a reasonable number of drug licence holders in the market, but shortages persist across all manufacturers of other lisdexamfetamine dimesylate capsules, except Takeda.

The improvements have not completely resolved the issues in the UK. According to the BBC, patients and pharmacists are still spending much of their day hunting for medication.

Interdependencies, Uncertainties and Risk – the Old Supply Chain Story

While the drug-shortage situation remains critical, root causes can always be debated. However, a number of facts are clear:

- demand is a key driver;

- manufacturing problems are not limited to the manufacturers – various regulatory agencies play a significant role in supply constraints;

- generics offer no quick fixes to shortages;

- and the interdependencies of the global pharma supply chains mean shortages in one country can quickly go global – pharma companies fish in a very small pool of suppliers that swim in dangerous waters.

But, then, anyone who has been paying attention already knows that. These are the challenges that SCAIR® has long sought to address. The battles over ADHD are just the latest in the long-running war to keep shortages at bay.