Onshoring or Pushing Against the Tide? Pharma will Struggle to Reconfigure Supply Chains

There’s no single strategy for resolving the massive uncertainty unleashed by tariffs and trade wars, but it’s essential to have one.

It looks increasingly likely that the pharma industry’s luck is running out.

The sector has successfully dodged tariffs and trade wars for years. Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariff announcements in April, though, may have been the beginning of the end. It escaped immediate tariffs, with its exemption continuing, but the President put it on notice.

“We’re going to be announcing very shortly a major tariff on pharmaceuticals. And when they hear that, they will leave China,” he told a fundraiser the following week.

That will hit many hard. According to Erin Fox, a drug shortages expert at the University of Utah, the biggest losers could be hospitals when low-margin drugs that are essential are discontinued because they aren’t economically viable to market. This will exacerbate existing shortages.

As the article under the headline makes clear, however, the key test for pharma may not be how well it braces for impact but how flexibly it can respond.

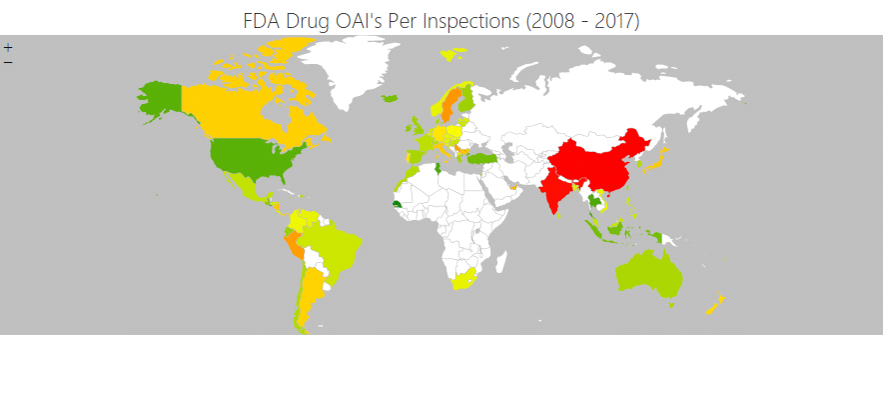

The historical record is not always encouraging here, but it has rarely had to be. The pharma industry has been able to rely on an increasingly globalised supply chain and increasing reliance on China and India for active ingredients and generics.

While it has not been free from disruptions (most notably in recent times due to Covid), the lack of tariffs on drugs, supported since 1995 by the World Trade Organisation (WTO) agreement, has kept supplies flowing.

If that’s to change, the industry will have to overcome some longstanding challenges.

Can Pharma Learn from Apple?

Few industries welcome new tariffs, but some, which are less regulated, can respond more nimbly than others.

Apple is among those already making radical changes to its supply chain, reducing reliance on China, the frontline for the trade war. It aims to have the majority of iPhones sold in the US manufactured in India by the end of next year (while 80% are currently made in China), according to reports. It’s also shifting to US-made chips as it looks to radically alter its supply chain.

Even before the April announcement, Apple chartered flights to ship 600 tons of iPhones from India to build up inventory in the US, lobbying Indian airport authorities to cut customs clearance from 30 hours to six.

Such fleetness of foot is difficult for the life sciences sector to replicate, however. Onshoring pharma supply chains is a far more complex affair.

The need for regulatory approval of sites serving the US significantly undermines attempts to rapidly reshape supply chains. Pharma manufacturers will struggle to find suitable suppliers with appropriate quality performance that are likely to be subject to (albeit lower) tariffs.

Technical transfer, process validation and FDA approvals for life science manufacturing sites are rarely swift, and with budget cuts looming, regulatory delays could increase. According to FDA commissioner Martin Makary, the agency has already laid off nearly 1,900 staff under restructuring prompted by the Secretary of Health and Human Services, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. However, Trump is trying to redress this issue in favour of US manufacturers with his recent announcement that will attempt to reduce regulatory barriers for domestic producers.

Even without delays, the costs involved in onshoring manufacturing are likely to prove prohibitive.

“Tariffs on pharma imports, as a measure to encourage nearshored manufacturing, are more than offset by the costs of relocation for drug companies,” as this piece puts it, citing Mina Tadrous, assistant professor of drug policy at the University of Toronto. Another academic estimated the time taken to recoup the costs of establishing US-based pharma manufacturing at eight to ten years. By the end of that time, Trump will be in his late eighties and the next US President, perhaps also retired or in their second term.

Troubles and Trade Deals

Difficulties, however, can no longer be a cause for delay.

Because, first, it’s not just China. Ireland (the world’s leading supplier of Botox, apparently) is bracing for the impact of tariffs. Even the UK, which this month became the first to agree a trade deal with the US since April’s announcements, only secured “preferential treatment in any further tariffs” for pharmaceuticals. If that’s what you get when you have a significant trade deficit with the US, it’s hardly encouraging for others.

Moreover, the US isn’t the only market the industry needs to worry about. A week before the US deal, the UK signed a more comprehensive trade agreement with India. That was widely welcomed, but not by the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI).

“The ABPI is disappointed that the deal does not appear to address longstanding industry concerns about intellectual property protections for UK life science innovators within the Indian market, particularly the need for regulatory data protection,” the association said.

Even without recent development, the potential impact of Trump’s antipathy to globalisation and onshoring has been an issue going on for close to a decade now. Inaction doesn’t seem like a viable strategy.

Big Pharma and Onshoring Efforts

In some cases, at least some big pharma companies are looking at the lay of the land and concluding that bolstering parts of their US manufacturing base makes sense:

- GSK is expanding its US operations, doubling capacity and adding new facilities to its Pennsylvania site, with a £800 million investment – its largest in the US to date.

- AstraZeneca, was ahead of the game back in March 2024 when it started planning for independent supply chains for the US and China. It already has 11 sites in the US and has said it’s planning even greater investments in the country. It’s now shifting manufacturing of the minority of medicines sold in the US that are imported from Europe onshore, according to its chief executive.

- Eli Lilly and Company, which has already invested billions in US manufacturing since 2020, has announced plans for four new pharma sites there, three of them focusing on manufacturing active pharmaceutical ingredients. “Upon completion of our manufacturing agenda, we’ll be able to supply medicines for the US market entirely from US facilities,” the company’s chairman and CDO has said.

US manufacturing isn’t going to be a solution for everyone. Neither is it a solution for everything; alongside its US expansions, Lilly is also expanding globally, bolstering manufacturing in Ireland and Germany.

The important point is not the strategy pharma leaders have settled on, but the fact they have a strategy at all, i.e., not bracing for impact but anticipating attacks on their supply chain resilience and viability.

The outcomes of that strategic planning will vary. It might mean shifting production domestically or, elsewhere in the supply chains, stockpiling critical drugs to buy time. It could mean exploring and exploiting customs duties workarounds like first-sale rules that allow duties to be paid on the first sale price of goods before they enter the US, instead of the price ultimately paid. It certainly means becoming informed of the country-of-origin’s customs rules that determine the duty that will be charged, usually, but not always, determined by where the API was produced.

As always, the starting point is gaining visibility across the supply chain and understanding the value at risk.

The changing outlook for tariffs, customs rules and new trade deals makes this more complicated but also more vital. With the outlook changing overnight, no strategy will fully stand the test of time, but that does not remove the need for planning. The point of supply chain resilience is not to eliminate uncertainty but to be able to live with it.