Pharma Supply Chain Risk: Why Assessing it Correctly to Minimise Disruption is Notoriously Tricky

Pharma supply chain risk and supply side failure can have catastrophic consequences for life science organisations – the results could have financial impacts as well as cost lives. Beyond developing treatments, it is the industry’s raison d’être to make drugs available where they’re required. A failure to do so is a fundamental flaw.

Globalised, complex supply chains make it challenging to avoid disruptions, but that only makes it more important to prepare for failure. Pharma businesses should concentrate on what they can control.

The risks of supply side failure are all too frequent. As this recent piece notes, there are currently over 200 drugs in short supply on the US Food and Drug Administration’s online drug shortage database.

Moreover, shortages have grown over the past decade. A study published last year by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine shows ongoing and active drug shortages are more frequent and last much longer than in the past.

It was cited in a letter by Republican leaders on the House Committee on Energy and Commerce to the FDA Commissioner in March, calling for action.

There are options for mitigating such shortages: sourcing an alternative supply and/or increasing stock levels to either carry through temporary disruption or switch to the alternative. In practice, both are costly, but alternative sourcing is complicated by limited options and, more often, by the ability to even identify the vulnerability and risk.

Several related factors contribute to the identification challenge – some common across industries, others more specific to pharmaceuticals and life sciences.

Assessing Pharma Supply Chain Risk - Common Issues Facing Pharma Supplies

Perhaps the most obvious factors that make achieving resilient supply chains across industries difficult, are the related issues of globalisation, supply chain complexities and concentrations of risk.

These impact life sciences just as other sectors, and more than many. We’ve discussed before Western pharma businesses' heavy reliance on overseas manufacturers, particularly China and India, when it comes to active ingredients.

Such globalised supply chains are perhaps unavoidable, particularly for low-cost generics, where margins require low-cost production centres.

But they mean that pharma supply chains are vulnerable to a wider range of risks than they would be were production onshore – whether that’s export restrictions by foreign governments, hurricanes hitting Caribbean islands, or the difficulty maintaining standards – and avoiding dreaded FDA Warning Letters in remote production locations.

Far from reducing globalisation, recent years have, if anything, accelerated it. US pharmaceutical imports from China (and exports to it), for example, are booming.

This contributes to the second challenge of complexity. Both risks and dependencies are more difficult to identify with supply chains that span the globe and can reach across industries – from laboratory facilities to farms.

Over a decade ago, for example, the life science industry saw a huge recall of heparin, an anticoagulant used to prevent harmful blood clots and extracted from pigs’ intestines, in small workshops based in China. This dependency may change in time with new production methods, but where animal derived products are concerned, this type of dependency is unavoidable.

Complexity may also disguise concentrations of risk – even if these are avoidable: Reliance on common manufacturers by a vast range of manufacturers is nothing new; one thinks again of the explosion in Shin Etsu’s manufacturing facility at Naoetsu in 2007 – disrupting the supply of chemicals for cellulose derivatives used by many major pharma groups for their tablet formulations and coatings. More recent examples are not hard to find.

Even where alternative suppliers exist, pharma businesses are left scrambling and competing for this extra capacity – at a minimum, driving up costs.

Pharma-Specific Supply Challenges

Other factors exacerbate these challenges. Some are, again, common across industries: The rise in just-in-time manufacturing and its spread from automotive businesses across industries has undoubtedly had an impact.

While reducing inventory may have merits in terms of efficiency, it is not necessarily well suited to complex, globalised supply chains. We’ve considered before whether time is up for just in time – at least when it comes to pharmaceuticals.

Other challenges also may affect pharma manufacturers more acutely, if not uniquely. One is the scale of manufacture: pharma and biotech companies’ influence over some suppliers is limited because the volumes purchased are often small – even while the supplies have a disproportionately high value at risk attached to them.

In the ordinary course of trading, there may be no issues; in times of crisis, however, perhaps due to soaring demand from other sectors sourcing the same supplies, pharma businesses can find they are a low priority where supplies are limited.

This can be a particular problem because the drug development process starts small, and sometimes specific sources will be identified in the regulatory dossier that are difficult to change post-approval.

And that leads us to the critical challenge that particularly affects pharma: The regulatory demands the industry faces.

On the one hand, as the reference above to Warning Letters and OAIs (Official Action Indicated) notices indicates, the rightly strict standards for pharma and other life sciences products contribute to the risk of quality issues and subsequent regulatory action.

Quality related issues remain the leading root cause of supply chain disruption historically.

At the same time, bolstered by the experience of Covid, government interest is also increasingly focussed on not just quality but continuance of supplies. In June, US Senators put forward a bill to force government agencies to investigate weaknesses in the country’s pharma supply chain and develop plans to reduce dependence on foreign countries. It is just the latest example of the trend towards governments pushing for increased resilience.

That these twin priorities – of ever stricter quality requirements, making setting up new production facilities prohibitively expensive, and continuity of supply on the other – may conflict, goes largely unacknowledged.

Mitigating Measures for Pharma Supply Chain Risk

The range and difficulty of these challenges should lead us to a critical conclusion: attempts to anticipate the specific events that lead to major supply chain disruptions are largely futile.

In general terms, identifying issues that may cause an interruption, such as the weather, political action or regulatory enforcement, may be possible.

In most cases, however, predicting the wide range of specific threats that might impact first, second or third-order suppliers is impossible. Even if it weren’t, most events that may affect their supply chains are outside companies' power to control.

It also suggests a solution because the risk is not simply determined by the chances of disruption – but also by its impact. The first is very difficult to quantify; the second is more feasible.

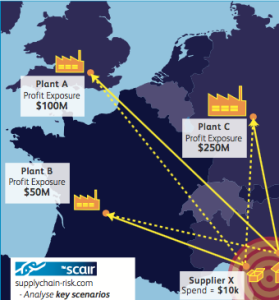

As a consequence, rather than looking to precisely predict the sources of major disruption, businesses are better off assessing their supply nodes: determining which are most critical by focusing on those that are unique or difficult to replace and estimating the potential loss from their disruption.

Quantifying that loss will help prioritise mitigation efforts.

This will also provide the justification – or otherwise – for the cost of mitigation, whether that’s investing in alternative facilities, holding more inventory or establishing alternative sources.

In truth, there may not always be a cost-effective solution for avoiding shortages. Onshoring prospects for low cost generics are particularly limited . Low cost drugs come with that price.

However, two issues should be noted: first, the visibility of the supply chain that the exercise promotes can also lead to opportunities to drive efficiency, particularly as technology advances; and second, whether mitigation is worth it, is a calculation that can only be made once you know the cost of failure.

And if you do not understand the value at risk at each supply point, your competition still might.