Drug shortages are back – or at least the risk is

That might seem alarmist. After all, the high point for shortages – at least in the US – was earlier in the decade, after shortages tripled in the years from 2005 to reach 251 new drug shortages in 2011. That led to concerted efforts by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and others, resulting in a steep decline in the following years.

Last year, according to the FDA’s annual report, there were just 39 new shortages.

Three factors, though, should cause concern. First, the risk has never really gone away; it’s just that efforts to manage it improved markedly following the President issuing an Executive Order in 2011 directing FDA to take steps to prevent and reduce disruptions in the supply of lifesaving medicines. That encouraged it to require drug manufacturers to provide advanced notice of potential shortages and expedite its regulatory reviews, for example.

It was further helped by passing of the FDA Safety and Innovation Act in 2012, giving the regulator new powers.

The risk, though, remains: in 2017, the FDA helped to prevent 145 shortages (up from 126 in 2016), and was notified of 520 potential drug and biological product shortage situations from 86 different manufacturers.

Second, as the FDA report notes, there are on-going shortages. While there has also been considerable success in tackling these, there remained 41 at the end of 2017.

Finally, while the number of new shortages is still modest compared to the peak a few years ago, the 39 in 2017 does represent a significant increase on more recent years. In fact, the 2017 figure is 50% up on levels in 2015 and 2016 when there were only 26 for each year.

Reasons for pharmaceutical shortages

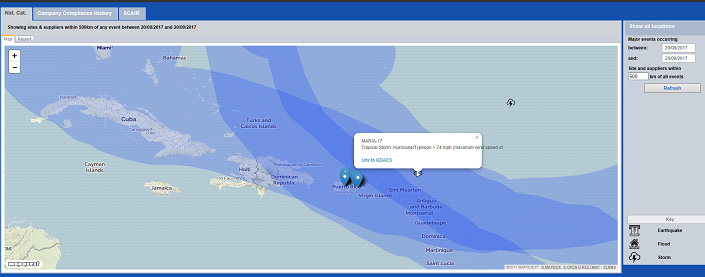

Of course, part of the surge in 2017 was the result of hurricanes Harvey, Irma and Maria. The latter two, particularly, hit Puerto Rico, home to numerous pharma manufacturing facilities, hard, creating both new shortages as well as worsening existing shortages, despite the FDA’s extensive efforts.

But these won’t be the last storms to impact the region, and there are structural problems, too. It’s not just the number of drug shortages that’s a problem, of course: it also depends which drugs are in short supply – and the combinations. As this article explains, for example, in some hospitals it’s not just that the go-to drugs for pain relief such as morphine, hydromorphone and fentanyl are in short supply – so are many of the alternatives.

“We’ve seen a variety of shortages over time,” the doctor explains. “What’s been challenging is that second-line drugs are out, too.” Research shows half of drug shortages are for medications used in critical care.

All of this helps explain why the FDA announced last month that it was setting up a new drug shortages task force. As FDA Commissioner Scott Gottlieb put it: “While we’ve made progress to mitigate individual shortages, we haven’t firmly impacted the underlying structural concerns that give rise to these recurring challenges. When shortages occur, practitioners are forced to ration supplies or substitute alternate drugs that in some cases compromise patient care. We need to pursue more enduring solutions.”

The new task force will explore why some shortages remain a persistent challenge, and look for “holistic solutions” to addressing the underlying causes for these shortages: including both what additional powers for the FDA could help ensure continued access to medicines, and policy steps that could address the root causes giving rise to shortages. Crucially, the statement notes that lasting solutions can’t be the responsibility of the FDA alone.

“Historically, many drugs in short supply have been low-profit margin generic medicines. Many are sterile, parenteral drugs, which can be challenging to manufacture. The low-profit margins, and the significant cost of manufacturing these complex drugs, has resulted in consolidation in the industry. The only way to produce these low-margin products profitably is to manufacture them at tremendous scale. This has resulted in fewer and fewer manufacturers for certain key products. The result is very little margin for error in this space.”

That suggests there’s not going to be any panacea, and that any solutions are likely to take time. The question then remains, what will happen in the years to come if President Trump is successful in his proposed 30% budget cut at the FDA; less resource to mitigate shortages if they happen or fewer enforcement actions resulting in fewer shortages in the first place?

Problems for UK pharma

And it’s not just a US issue, of course. UK pharmacists have also been complaining of significant shortages for months, if not a year, particularly for certain classes, such as diabetes drugs.

That has a number of effects. Most obviously, of course, it’s bad for patients. It causes unnecessary additional distress and forces doctors to use less effective alternatives or those with greater risk of bad side effects.

“It's a patient safety issue,” says the chairman of the national clinical governance board for US Acute Care Solutions physician group.

Second, it adds to cost. The Times report on shortages at the end of last year noted that they cost the NHS £180 million in six months alone, threatening to swallow the entire winter funding bailout for the UK’s health service. At the very least, shortages jeopardise the negotiating power of providers, and the drive to control costs. As one local pharmacists group explained, there were particular issues around the supply of generic medicines stretching back to late spring last year – partly due to the closure of two generics manufacturing plants, but also due to the success of the NHS in driving down prices in the past.

As it wrote: “Generics prices in England are incredibly low compared to most parts of the world, because DH’s [the Department of Health’s] policy to incentivise community pharmacies to reduce medicines prices for the NHS has worked incredibly well. There is a global market for generics, so international manufacturers can choose to sell where they will make the best financial return.”

Finally, and not unrelated to the issue of rising costs, shortages create extra work. Hospitals and pharmacists have to seek out alternatives; patients waste time trying to get drugs that aren’t available; and GPs have to spend time rewriting prescriptions for alternatives.

Brexit and trade wars: time to stockpile essential drugs?

Just as in the US, the problems in the UK aren’t going away any time soon. In fact, there are significant fears the shortages will get worse if there’s a no Brexit deal. In July Sir Michael Rawlins, chairman of the Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency warned that Britain could face significant shortages of drugs such as insulin in the event of no deal.

The UK imports “every drop” of insulin it uses, he warned, creating a risk for 3.5 million with diabetes who rely on it, including Theresa May, the Prime Minister. The new Health Secretary Matt Hancock, meanwhile, has said there are plans in motion to stockpile drugs, as well as medical devices and blood products in case of a no deal exit.

Brexit could affect not just Britain, however. Its neighbours could be hit, too. In August the head of the Irish Pharmacies Union called for drugs to be stockpiled to minimise disruption in the supply chain from Britain. Six out of ten of the drugs in Irish pharmacies are manufactured in the UK or labelled there, she said.

“The UK is obviously the largest English-speaking country in the EU and 37 million patented packs of drugs go into the UK every month and 45 million come out. That is 1 billion per year.”

Whilst on the subject of barriers to trade, the US’ tariff war with China could also threaten continuity of supply owing to the dependence on the US market for Chinese contract active pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Forward thinking - managing drug shortages

All these issues are putting increasing pressure on everyone in the pharma supply chain. Whether it’s simply to prevent shortages for patients, control costs, or meet growing regulatory expectations, the issues are growing more complex, and the risks greater.

In this scenario clarity on the evolving risks is going to be increasingly important, and technological solutions such as our Incident Monitor module can help: collecting supply chain interruption information from previous recall warning letters, product shortages, import alerts and GMP non-compliance reports from leading medicines regulators such as the FDA and EMA.

With a history of the supply base’s quality performance, businesses can identify repeat offenders by company name, and use analysis to identify root causes – whether that’s for drugs, biologics, veterinary or medical devices. It can also analyse different product characteristics (therapeutic area, dosage form and route of administration) to determine which product types are most likely to trigger non-compliances.

The benefit of this approach is not just that it enables businesses to better manage the risks; but also that it allows them to track how the risks are evolving. That’s going to be increasingly valuable – partly just because shortages are becoming increasingly problematic; but also because the one thing that’s already clear from developments within the FDA and around Brexit is that things are capable of changing pretty fast.