Trump and Trade Wars: An Uncertain Future for China’s Pharma CDMOs and Global Supply Chains

Renewed China tensions and the US Biosecure Act are creating new uncertainties for biopharma supply chains. However they play out, businesses will need visibility of the exposures to mitigate the risks.

China is determined to become a leader in biological sciences, but will the world let it? Can it stop it?

Long a leader and key link in global supply chains for active pharmaceutical ingredients and generics, the country has even greater ambitions. The government is heavily backing the bio sector. At the government-hosted National Industrial and Information Business Conference held in December in Beijing, bio-manufacturing was among the priority areas identified for policy support in the coming year.

BIOCHINA2024, meanwhile, an event for the biotechnology and pharmaceutical industries hosted a few months earlier, welcomed almost 28,000 registrants, 480 exhibitors, and 839 speakers.

In fact, the question is not whether it can become a leader in biologics but the leader. It is already a massive player. According to a report by analytics company Clarivate, the country is now responsible for 23% of the global pipeline of innovative drugs.

“Mainland China’s biopharmaceutical industry is scaling, facilitating advancements in healthcare accessibility and affordability through multi-level medical security systems and streamlined drug approval pathways,” the analysts note.

China CDMOs – doing the work

That’s reflected in the growth and success of the country’s flourishing contract development and manufacturing organisations (CDMOs), offering outsourced drug production and development capabilities.

The life sciences industry has increasingly relied on such organizations to boost its flexibility, speed-to-market, economies of scale and resilience. Once a client uses a CDMO in a drug’s development stages, it is likely to stay with it through scale-up into commercial manufacture.

That’s a boon for the CDMO’s future revenue streams.

The global CDMO market, estimated to be $140 billion in 2024 and $115.5bn at the start of this decade, is forecast to grow to $223.5 billion by 2030. Some giants, like Gilead Sciences, are entirely reliant on contract manufacturers. Many others have been ramping up their use. As the FT noted, Merck, GSK and AstraZeneca signed licensing deals worth $44.1bn in 2023 alone.

China has some of the leaders in that field, such as WuXi AppTec and WuXi Biologics, among the largest CDMOs in the world. Unlike with generics and APIs, their success is not simply built on lower costs. They have high-tech facilities and a massive commercial advantage in being able to take a novel biologic from development, through scale up to full scale commercial production. It’s not surprising that they have relationships with many of world’s top biopharma businesses.

The US Biosecure Act

WuXi AppTec and WuXi Biologics are among the companies to have attracted the ire of US law makers, however.

Driven by both specific controversy of unauthorised transfers of US companies’ intellectual property to China and the background of increasing – and bipartisan – concern over the reliance of pharma supply chains on the country, legislators have acted.

In September, the US House of Representatives passed the first vote on the Biosecure Act, which would prohibit federal contracts with several named Chinese groups – and those that do business with them. The companies named include WuXi AppTec and WuXi Biologics, as well as Beijing Genomics Institute (BGI), MGI, and Complete Genomics.

In the House, as Reuters notes, the bill passed convincingly by 306 to 81. It now needs to be passed by the Senate, where it was received in October and has had its second reading. It’s now currently referred to the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs.

Even before passing, it’s already had an effect. The affected companies have seen share prices slump and are seeking to sell off their sites in the US and Europe. In January, WuXi Biologics agreed to sell its Irish vaccines factory to Merck for $500 million, much less than expected. A month earlier, WuXi AppTec announced it was selling its overseas-based cell and gene therapy business to New York headquartered healthcare investment firm Altaris LLC.

Mixed messages, Trump and China

Of course, from the point of view of China’s CDMOs and some who rely on them, the worst might not happen. The Biosecure Act has still not passed. Its provisions were left out of both the 2025 National Defense Authorization Act passed in December and a Continuing Resolution later that month. That pushed any legislation into the new year, and now, since the inauguration, under a new administration.

It is true that neither Trump nor the Republican party, which controls both the House and Senate, are likely saviours of Chinese pharma manufacturing. As we’ve discussed before, antagonism towards Chinese trade was a key feature of the first Trump administration and the second promises more of the same. Moreover, as noted, much of the concern over reliance on China for US pharma manufacturing is shared across both US parties.

There is still the possibility that the US might back away from what some say would be an act of self-harm, however. As one commentary put it, “There are concerns that the Biosecure Act could raise drug prices higher due to the pharma companies not having access to cheap manufacturing sources or partners within their supply chain, along with the costs of transitioning to different manufacturing partners.”

Nevertheless, given the recent rhetoric and long-term trends, you probably wouldn’t bet against some action impacting Chinese CDMOs from the US in the coming year. The sales of overseas assets by WuXi Biologics and WuXi AppTec suggest they’re not.

International (in)action: Reactions elsewhere to China pharma

But what about outside the US?

In some ways, the long-term trends in Europe are little more encouraging for China’s CDMOs. Europe has not yet legislated for biopharma sanctions. But there are signs it’s on the same road as the US, just a little further behind.

After all, the origins of the recent wave of concern over reliance on China and other offshore manufacturers are strongly linked to the Covid crisis. Europe was far from immune to the vaccine nationalism that swept through many countries at the time. With the CIA now adding its endorsement to the lab-leak theory for the origins of Covid, suspicions of China pharma reliance are unlikely to ease in the short-term.

Moreover, Europe shares the more general US unease with its trade imbalance with China. China is the EU’s largest trading partner after the US, but with a persistent trade deficit: China is the EU’s third largest market for exports, valued at €233.6 billion in 2023, but its biggest for imports, which were more than double that in the same year, at €515.9bn.

The EU Commission is less bellicose than Trump, but it clearly shares some of his frustrations: “Our economic relationship is critically unbalanced, both in terms of trade flows and of investment, due to a significant asymmetry in our respective market openings. In addition, China’s economic model has brought about systemic distortions with negative spillovers to trading partners. According to the IMF, China’s use of industrial policies, notably its support to priority sectors, has an impact on trading partners,” it states.

China confidence: Already a biopharma giant

If there is a showdown with the US or Europe, there’s little guarantee China will back down. The Chinese biopharma industry certainly has global ambitions, and these will be challenged by the US Act if it passes and potentially by other action.

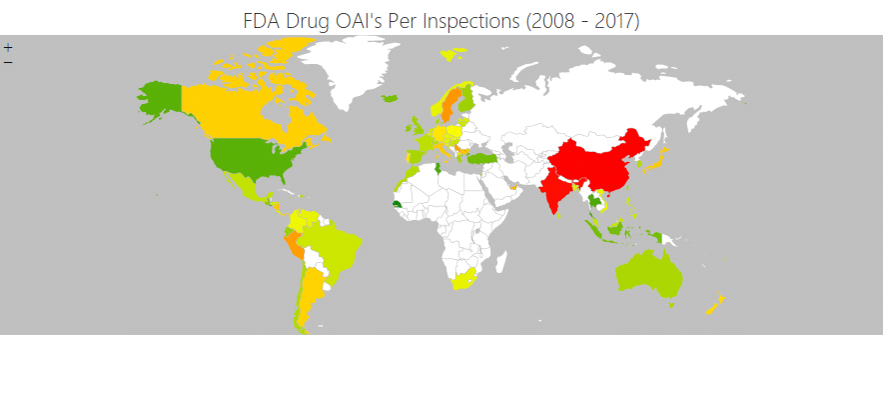

However, it’s important not to underestimate how far China’s industry has come. It is already the world’s second-largest medical market, and if US action is not closing the gate after the horse has bolted, it’s certainly come too late to nip it in the bud. In the past, the US FDA banned substandard Chinese imports. Today, China’s regulators flex their own muscles by banning Indian suppliers.

As one commentary notes, “While the Biosecure Act introduces formidable challenges, it also presents opportunities for Chinese biopharma companies to pivot and innovate. To mitigate the risks posed by potential sanctions, these firms can adopt several strategic countermeasures.”

These include turbocharging domestic R&D to reduce reliance on international research cooperation and strengthening domestic supply chains.

The strength China has already attained may also mean countries less powerful than the US may choose not to follow its lead and instead opt for a more conciliatory approach. In light of the Chancellor of the Exchequer’s recent visit to Beijing (despite some criticism), that could be the approach the UK government is taking. Following the meeting, the government announced that China had agreed to consider expedited approval for the RSV (respiratory illness) vaccine for adults over sixty years old – a boost to the UK’s pharmaceutical industry.

It is, of course, still too early to know how the latest round in the China trade wars will turn out. With such uncertainty, though, one thing is sure: Pharma businesses need to know their financial exposure to contract manufacturers in China, directly and in their supply chains. And they need to understand the implications of any supply chain mitigations, such as delays while bringing in an alternative source.

SCAIR® enables you to model such dependencies accurately and calculate the real values at risk. Whatever China, the US, Europe or the UK do, it will be a valuable tool in the months ahead.