The Complex Truth Behind Vaccine Nationalism

No winners in the short term

Vaccine nationalism shows no signs of going away, and moves to re-shoring in certain parts of the pharma industry look certain. While that may bring some benefits in the long-term, there will be downsides. Either way, don’t expect it to deal with drug shortages.

The row continues. With the EU on Thursday stopping short of vaccine export bans but backing more stringent export controls to pressure AstraZeneca to "honour its contract". The rhetoric around vaccine nationalism is not improving. Earlier in the week, the Commission confirmed plans for all vaccine shipments to be assessed on the destination country's rate of vaccinations and exports. Talk now is trying to achieve a win-win, but in truth supplies from the Halix, Netherlands, factory due for delivery to the UK remain at risk.

According to one data analytics firm, a ban could delay the UK vaccine drive by two months – without necessarily bringing much benefit to the EU; the number of vaccines in question would only accelerate its efforts by about a week. It could also impact the capability of other vaccine manufacturers used by the EU, were the UK to retaliate; Pfizer has warned that its production on the continent relies on materials shipped from Yorkshire. In particular, Croda International, a chemicals firm based in Staith, Yorkshire, provides Pfizer's factories with the fatty molecules its vaccine needs.

As the UN-backed global vaccine alliance Gavi has warned, export bans could “prolong the crisis, add to our economic difficulties and lead to further loss of life”. And that’s before we consider any potential escalation into a wider trade war.

Frankly, the bigger problem the EU may face in its drive with the AstraZeneca vaccine is public confidence. That has plummeted in Europe, following the hopelessly mixed messaging from political leaders and public health bodies over recent weeks over its safety and efficacy.

In the short-term, then, there’s little benefit to be discerned from the wave of vaccine nationalism that even the WHO is warning against. In the long-term, though, recognition of the weakness in some supply chains and limited capacity to deal with such a crisis might encourage some useful changes.

Moves to protectionism and export bans only threaten to undermine pharmaceutical supply chains; indeed, a central complaint against the EU is that it is, as one commentator puts it, “taking a sledgehammer to something brittle”. Many EU leaders have urged caution. On the other hand, countries’ efforts to develop domestic production could provide a constructive approach to boosting capacity and building resilience.

A big shift

Well, perhaps.

Certainly, there seems little doubt that the reshoring of some pharma production will outlast the current crisis.

Moves to address this and develop domestic capability, therefore, predate the current row. Last year alone, the UK government announced investments in vaccine manufacture of over £240 million. October saw building of the first national Medicines Manufacturing Innovation Centre (MMIC) begin up in Scotland. The government’s also working with generics Wockhardt on fill and finish services as part of the effort to accelerate vaccine manufacturing in the UK. Other plans are also in the pipeline.

These plans are for the long term. In part, that’s because Covid may require vaccine production capacity for years to come, with new vaccines and boosters to deal with resurgences and mutations. It’s also because Covid has highlighted just how little production capacity countries such as the UK had in place.

There are long-term trends working against the continued reliance on outsourced centres, too. Outsourcing production to low-cost locations such as China does rely on them continuing to be low cost. With a growing middle class there and rising wages, that won’t last forever. The average wage in the country is around 90,000 yuan – still under US$14,000, but more than double its level a decade ago. And China looks set to have weathered the Covid crisis much better than most: Growth in the country is set to top 6% this year.

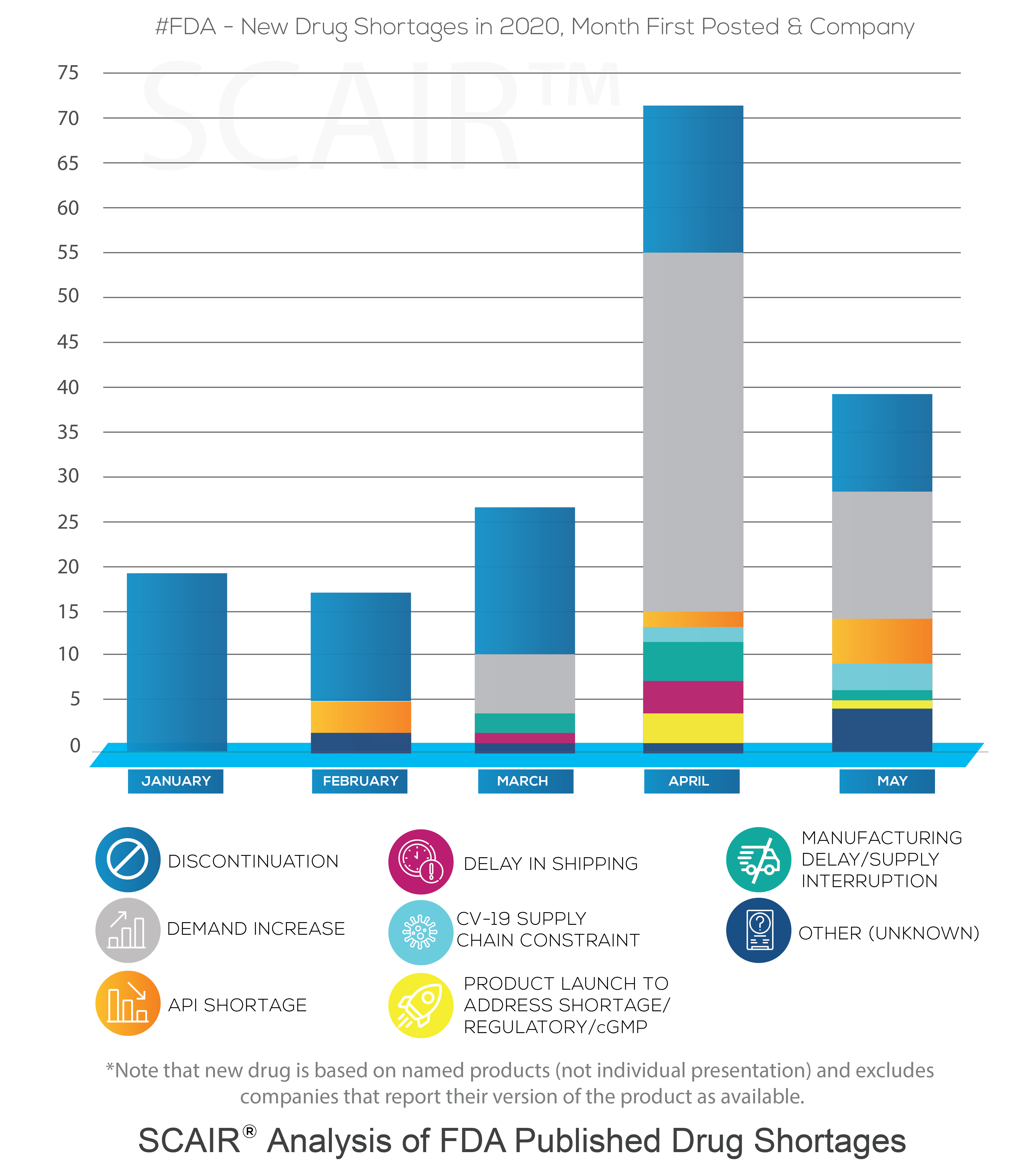

However, there is also the issue of drugs shortages, which predates the pandemic and can only be solved by increased capacity and diversity of supply. The last year’s crisis has merely been the jolt to turn plans to address supply chain vulnerabilities into action.

The UK's concerns about outsourcing pharma production are echoed and perhaps magnified across the Atlantic. The US government has made no secret about the fact that it considers reliance on outsourcing drug production a national security issue. A case in point would be The Commissioner of Food and Drugs at the FDA Janet Woodcock’s testimony at the hearing of the US-China Economic and Security Review Commission where she declared: "...use of foreign-sourced materials creates vulnerabilities in the U.S. drug supply".

No quick fix

All this is true as far as it goes. When it comes to supplies and development of sophisticated vaccines, there’s little doubt the UK – and other countries – will be on a better footing for the next crisis if it comes. We should, though, be wary of drawing conclusions that are too broad.

For a start, as the current dispute is showing us vividly, there are no quick fixes. As we noted last month, the problems illustrate the enormous complexity and uncertainty of some of the manufacturing processes involved. Ramping up and establishing production lines in existing facilities takes time; building new facilities takes even longer. In many cases, we’re talking long-term capital projects, taking 18 months or more before even opening the doors. The current efforts will have an impact on national capabilities, but the changes won’t all happen overnight.

Efforts to boost pharma production capacity are also likely to come up against constraints – not least because we’re seeing so many countries seeking to boost their capabilities at the same time. Traditional pharma production centres such as India are also ramping up production; the Serum Institute in India (which makes the AZ vaccine) is the largest vaccine production facility in the world.

Among the key challenges is going to be finding the labour they need. The UK, in common with other countries, faces a long-term shortage of skilled workers to fill engineering and other key technical roles. Even before the pandemic, the Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry warned that the UK risked falling behind the rest of the world in terms of students studying STEM subjects. With the advent of Covid, there are likely to be fewer opportunities to recruit internationally to make up for domestic shortages. Brexit might not help, either, if it limits businesses’ ability to recruit from abroad.

Quality not quantity

But will they even want to?

The key question is where the investment needed to reshore pharma manufacturing capacity will come from – and how well that’s going to match up with the UK’s needs. The answer may be, not quite as much as some expect.

On the one hand, there’s little doubt that the UK government’s actions, in common with others around the world, will significantly boost our capabilities to product vaccines for Covid and other similar diseases. We can speculate, too, that a wider resurgence of onshore pharma production might benefit from support as part of the government’s “levelling up” drive to spread growth across the UK.

The problem is that there’s a fundamental mismatch between the sort of production that’s likely to be attractive to governments and the products where we most often see a problem with supplies. Outside the pandemic period, it’s not new, cutting-edge vaccines and drugs we run short of: It’s low-cost, low margin generics. They’re hardly the engines of growth and highly skilled jobs that governments tend to promote. Production of these moved to low-cost offshore centres for a reason.

So, if not governments, then what about the pharma industry itself? Well, if the sounds coming from the US are anything to go by, there’s little appetite there. As this piece notes, pharma companies aren’t convinced by the economics; “The industry's reasoning isn't complicated: Manufacturing stateside would likely cost a princely sum compared with the cheaper wages and lower costs abroad, and would upset the balance of pharma's global supply chain.” Moving all manufacturing to Western markets is “impractical and likely not feasible”, according to the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA).

There’s little reason to suspect European manufacturers will feel any differently. If anything, all the talk of export bans is likely to make them even less keen to relocate much of their manufacturing capability to more tightly controlled markets.

That’s not to say there will be no benefits from the renewed interest in domestic development and production in markets like the UK and US. Government support is likely to help the industry develop. It’s not just promoting new vaccines and treatments, but also prompting improvements in technology and production processes – helping the drive to continuous manufacturing, for example.

But it’s more likely to be an evolution than a revolution. Dependence on cheaper offshore production centres for many drugs will remain for the time being – as will the risk of shortages of generics on which so many depend. The vaccine wars will eventually see a truce. When it comes to tackling wider supply chain vulnerabilities, though, the industry faces many battles ahead.