The Real Reasons for UK Drug Shortages

What is Causing the Current Drug Shortages in the UK?

A recent BBC Radio File on 4 programme highlighted the worsening drug shortage problem in the UK . In this blog post, Intersys Risk Director Catherine Geyman further analyses the various complex issues that are driving this healthcare crisis.

“Patients have died in hospitals because of these shortages.” That was the stark message from BBC Radio 4’s investigation of UK drug shortages for File on 4 on Tuesday.

The programme is well worth a listen. It powerfully gave us a human face to the problems these shortages cause in the form of Michelle, who has trouble getting epileptic drugs to control her seizures; or the mother relying on an out-of-date, and therefore unreliable, adrenaline injector for her son.

It also does a good job of exploring some of the reasons. These include the restrictions on pharmacists – unable on their own initiative to even prescribe two 250ml dose pills of the same medicine where 500ml pills are unavailable. One striking nugget: The Serious Shortage Protocols, which I examined on this blog in July and which empower pharmacists to make this kind of substitution, have so far been introduced for only one drug – antidepressant Fluoxetine.

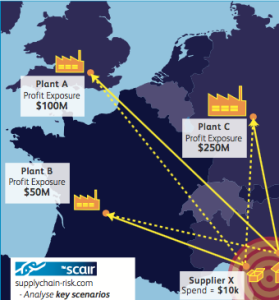

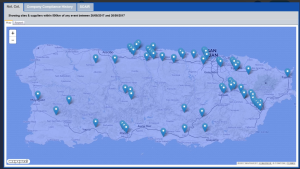

As the programme made clear, though, the reasons for shortages are complex, and there’s no quick fix. The central issue was particularly well captured in one part of the report: “One issue that is mentioned by pretty much everyone you speak to in the industry is globalization; making drugs and distributing them is now a huge, worldwide business. The longer the supply chain is stretched, the more fragile it becomes.”

It is the many and varied problems with the supply chain that are usually behind these shortages. I’ve looked at this before in relation to HRT medicines and adrenaline injectors – both shortages that featured in the programme. It’s manufacturing problems that are often to blame here, and indeed, according to the European Healthcare Distribution Association are responsible for 60% of medicine shortages.

Current drug shortages, but long-term issues

There are, though, perhaps two issues that we would take with this analysis. The first is that none of this is really new. It’s been clear for a while that medicine shortages are back in a big way, and most of these causes have been well explored already.

That, though, is possibly unfair; it's always good to raise awareness of these issues – and not just with the general public. One of the new developments reported by the programme was that the UK’s Healthcare Distribution Association is sending a leaflet explaining the complexity of the supply chain to all 16,000 of the country’s pharmacists. That suggests a lack of awareness even among those directly involved.

A more fundamental problem is that globalisation and complex supply chains – which are both longstanding – don’t sufficiently explain the number and extent of shortages we’re seeing now. Sourcing active ingredients from China and India is nothing new, after all. We could blame Brexit, of course, but the evidence for that being a significant contributor to even current drug shortages is weak.

One possible cause that could be further explored is the current high levels of mergers and acquisitions in the industry. As we’ve seen before, poor due diligence when it comes to takeovers can result in years of problems. More simply, this consolidation inevitably reduces the supply base – indeed in some cases M&A is specifically designed to reduce competition, decreasing the number of drugs available for particular conditions and increasing dependency on those that remain. That inevitably reduces the resilience of the supply chain.

It’s not all about cost

Even here, though, the issue is more complex than it might seem. In some cases, it’s true that supply of drugs for some conditions is down to just one or two producers. Inline with the programme’s perspective, that consolidation is the result of drives to cut costs, but that is only half the story.

First, the manufacture of complex drugs can be difficult and expensive, and the low cost of generics fails to incentivise more players to enter these markets. But, more crucially, that cost never rises. The FDA’s recent paper on Drug shortages suggested evidence of a “broken marketplace” – where a shortage of supply does not result in the price increases predicted by basic economic principles.

And this may have something to do with another point: The extensive regulation of the industry. Regulators have strict codes of practice in place and these vary according to the market that businesses are selling to. That means manufacturing certain drugs requires significant expertise and knowledge of relevant local regulation. This in turn means a long lead time to set up and get approval for new manufacturing assets to alleviate the issue – with no guarantee for those doing so, that the shortages will persist long enough for them to profit.

There’s a myriad of other issues, too, of course, but these should amply illustrate two points. First, that there’s no easy solution and this problem will be with us for some time. And, second, that all manufacturers and others can really do for now is use the tools available to really interrogate their supply chains and achieve a clear view of their resilience and the likely areas of weakness.

Catherine Geyman, Director, Intersys Risk Ltd.