The Climate Change Impact on the Insurance Industry: Understanding Business Interruption Threats and Finding Solutions

Climate change is a slow-moving crisis that could one day overshadow current complex supply chain risks. In fact, a large number of insurers and clients may not fully realise the value of climate-related exposures already building in supply chains and business interruption (BI) portfolios. However those who choose to ignore the climate change impact on the insurance industry, do so at their own risk.

In line with Taskforce on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations, since April 2022, it has been a legal requirement for over 1,300 of the UK’s largest public and private companies to quantify and disclose the climate-related financial risks and opportunities they face. This includes many large insurers, who must prove they understand how climate change risk might affect their insurance portfolios. The BI exposures alone – for example for the increased number of severe individual natural catastrophe events – could be extremely significant.

So How Big is the Potential Problem?

The climate change impact on the insurance industry is finally being quantified. Reinsurance and insurance provider Swiss Re Institute recently highlighted climate change as the biggest long-term threat to the world economy. They claimed it could reduce global GDP by 18% by 2050 if no mitigating actions are taken; 11% if global warming is kept to a 2°C increase on pre-industrial temperatures; or 4% if Paris Agreement targets are met (under 2°C).

Asian economies would be hardest hit, it said, with China – a massive producer of components vital to the global manufacturing supply chain – at risk of losing nearly 24% of its GDP in a severe scenario. The US, meanwhile, could lose close to 10% of its GDP and Europe almost 11%.

However, climate change isn’t just projected to impact (re)insurance. The industry has already experienced the direct financial impact of climate change-related weather events: according to Swiss Re, six of the costliest years ever for weather-related insured losses occurred between 2011 and 2021.

Business insurance has significantly exacerbated the financial fallout from these events, and risks to global supply chains become greater as climate change worsens. For example, McKinsey projected that the likelihood of a hurricane sufficiently powerful to disrupt semiconductor supply chains may grow by two to four times by 2040.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) also warns extreme weather and global warming will increase prices for essential goods. In 2022, we were given some indication of how that feels. Inflation could get worse if floods, droughts, wildfires and extreme weather leads to new energy shortages, political upheaval and trade disruptions.

Why Finding an Answer is Complex

It requires complete supply chain transparency to identify a high-risk supplier sitting in a hazard zone. However, the more difficult part is identifying how loss patterns will evolve over time; for instance, which new sites and suppliers could be exposed to climate-related perils in 10-, 20- or 30-years’ time? A place that may only have limited exposure to physical peril today could, a few years down the line, be in a drought, flood or wildfire zone.

Working out which sites and suppliers in supply chains could be impacted, and the financial implications, is paramount for insurers and supply chain-dependent clients alike. But make no mistake: it is not an easy task.

Quantifying BI exposures in supply chains and insurance portfolios is already complex. Many multi-billion-dollar industries, including batch and complex manufacturing, pharma, biotech and medical devices, rely on complex multi-supply chains, with interdependent suppliers situated across the globe. The shortage or delay of an input component costed at a few dollars manufactured in one region, can result in millions in lost profits and BI claims downstream.

Developing a Methodology to Identify, Manage and Track Supply Chain Exposure

First, it is important to discover which supply nodes are critical to the manufacture of goods and what physical and non-physical threats they are exposed to. Improvements in the granularity and availability of data is helping to identify geocoded property attributes such as elevation, building materials and transport links – or even non-physical factors like political or compliance risks – to further refine the risk assessment.

Once risks are correctly identified, mitigations should be put in place to manage those risks (such as stock redundancies, alternative suppliers and adaptive protective measures). This then feeds into a projection of the total profit at risk from any supply chain disruption. These exposures and outage values must be monitored continually and revisited at both a client and portfolio level.

It is good practice to overlay climate change scenarios onto those calculations, because the profit at risk in these scenarios will vary significantly. With their modelling capabilities, insurers are in a good position to help clients with these assessments. Not attempting this will increasingly be seen as negligent – illegal even – though it is not as straightforward in practice as it sounds.

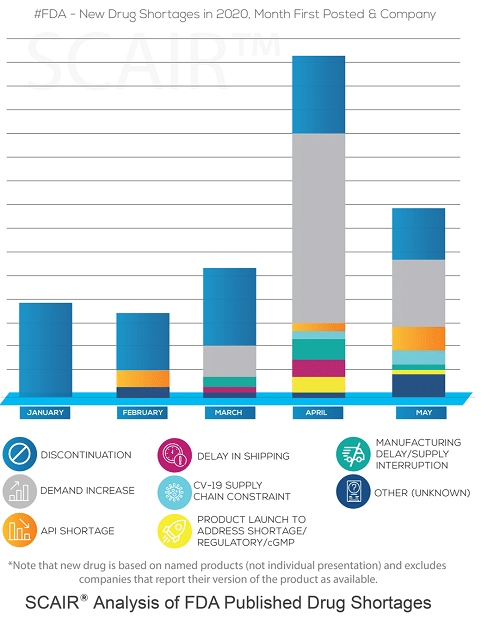

Supply chain risk assessment software solutions such as SCAIR® incorporate natural catastrophe alerting to help businesses identify major geographical risks within their supply chains.

Climate Scenario Modelling that Integrates with Supply Chain Risk Assessment

As loss patterns evolve, traditional weather and catastrophe exposure models based on historical losses become more and more redundant. Consequently, insurers need reliable predictive models so they can project future losses across various global warming scenarios.

The biggest and most sophisticated carriers and cat modelling firms are indeed making good headway on this; many insurers already use Munich Re’s NATHAN, for example, or other third-party modelling tools for their predictive climate scenario capabilities, though many are still figuring out how best to embed climate change risk into their processes.

Soon, it will be possible to integrate climate scenario models from leading providers straight into supply chain risk assessment tools. With this in mind, insurers must recognise the value this will bring – from enabling reporting and compliance and helping clients manage risks more effectively, to selecting and pricing risks more accurately, setting appropriate limits and avoiding unmanageable BI exposures aggregating.

The past 12 months have shown us climate change is not a risk coming our way – it is already here. Insurers must start mapping and quantifying the risk this poses to supply chains today, or the financial implications they and their clients could face tomorrow will be more and more severe.