The thing about the hurricane season is it’s always easy to speak too soo.

We noted a couple of weeks ago that Puerto Rico, a key production centre for pharma manufacturers, had escaped the worst of hurricane Irma.

Yet the clean up wasn’t even finished when the island was hit by the worst storm in 80 years, Maria, bringing “total devastation”. A number of factors have left the island particularly hard hit: Already fragile infrastructure leaving most without electricity – for weeks and many possibly for months; even cell phone coverage is limited; and widespread flooding has been exacerbated by the failure of the Guajataca Dam. The island also already filed for bankruptcy earlier this year, leaving it poorly prepared to tackle the costs of getting back on its feet.

Hurricane Maria might also have proved that it was a bit early to congratulate the industry and governments for avoiding drug shortages following Irma and Harvey. On Monday, the FDA warned that shortages could occur if the Puerto Rico pharma industry wasn't helped to get up and running quickly.

“The island is home to a substantial base of manufacturing for critical medical products that supply the entire world. This industrial base is an important source of jobs and economic vitality for the island. It is a key to Puerto Rico’s economic recovery. The manufacturing facilities are also a pivotal source of critical medical products for the entire United States,” its statement read.

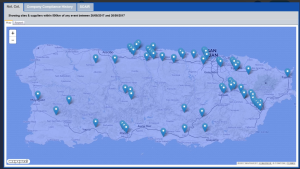

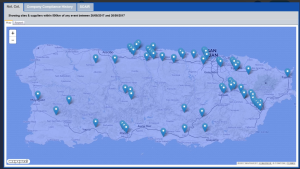

The problem, as ever, is both the scale of the storm – a “catastrophic event unlike many the United States has faced”, as the FDA put it – but also the scale of pharma manufacturing in Puerto Rico. That’s shown in a map taken from the tool in our SCAIRTM software of FDA Registered Drug Establishments affected:

With such a concentration in an area so prone to tragedy, the challenge for the industry to maintain supplies will alway be substantial.

Severe Weather Tests Supply Chain Contingency Planning

There certainly is a spectrum of views on the UK’s ability to plan for and react to extreme weather events. These range from the average man on the street complaining that the UK will always grind to a halt after only 1 cm of snow, to the opinion that we are learning from previous cold weather experience and beginning to become more resilient as a nation.

The recent performance of BAA and Northern Ireland Water suggest that the contingency plans of some infrastructure organisations have not accounted for extreme disruption scenarios. However, there may be some small glimmer of light at the end of the tunnel in the form of a review of the local authorities’ response to this year’s cold snap. This complementary report indicates that the local authorities have learnt lessons from the previous two winters.

Can any differences in performance between local authorities and infrastructure organisations be attributed to the difference in mandatory contingency planning requirements for first responders (governmental bodies, the NHS) and second responders (utility companies)?

Or is it more to do with the level of scrutiny following the disruption during the previous two winters (reported to cost the UK economy £1bn), which resulted in the Winter Resilience Review (final findings published Oct 2010)?

Either way, UK Plc appears to have applied some sound supply chain risk management principles in order to improve their local response efforts to the December snowfalls, namely:

- Alternative sourcing options. By exercising ‘contingency’ contracts, farmers and their tractors were quickly mobilised with their snow ploughs to clear the highways.

- Increased buffer stock. Following the well-publicised shortage of gritting salt last year, the government has taken decisive action to increase the national salt stock pile and then make local authorities pay through the nose if their own stocks are inadequate and they need more in a hurry.

As with most supply chain contingency planning, it’s all about justifying the investment in the solution by quantifying the potential impact of the threat.