Out and about at CPhI Worldwide

Greetings from Frankfurt where we've been at CPhI Worldwide.

We’re just returning from a successful week taking SCAIR to 36,000 pharmaceutical professionals.

You don’t have to be at the conference long to appreciate the importance of technology: The event brings in participants from every part of the pharmaceutical manufacturing and delivery, with over 20 dedicated zones covering ingredients, APIs, excipients, packaging, biopharma, machinery and so on. There are also participants from over 150 different countries.

Visiting this conference, it’s impossible not to get a sense of the both complexity of the modern pharma supply chain and its truly global nature. With new innovations announced every day at the conference, you also get a sense of how fast moving it is.

CMO uncertainty

And you get a sense of the risks: The annual report of the event’s organisers picks up on some of these, including including political uncertainty in the US, with a new administration that has shown a “keen political desire… to reduce drug prices, but with very little indication of policy”.

That’s left pharma companies and the contract manufacturing (CMO) “in the dark”, the report notes, and vulnerable to decisions that could disrupt their entire business model.

We’re at CPhI to show how technology such as SCAIR can address this type of risk, as well as more long-standing challenges that affect operators across continents and across the supply chain.

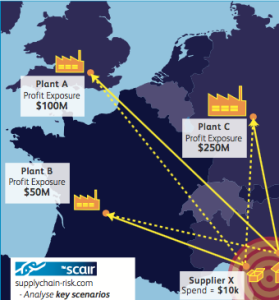

We don’t pretend to be able to control Trump, but SCAIR can enable businesses to quickly get to grips with the impact any changes may have. With the software they can visualise their end-to-end supply chains and quantifying accumulated exposures of the company’s product portfolio to each critical supply point.

Nat cat and compliance

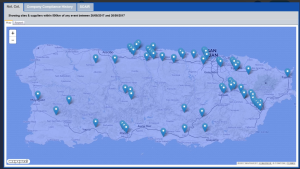

This Supply Node Exposure module in the software is also used to identify locations critical to the company for natural catastrophe alerting. Warnings and reports of hurricanes, earthquakes and floods are overlaid on these locations to rapidly highlight potential losses.

Finally, SCAIR deals with another key concern across the industry and highlighted frequently at CPhI: Compliance. It collects and consolidates non-compliance and supply chain interruption information from leading regulators such as the FDA and EMA. Root cause analysis of data such as recalls, production shortages, enforcement actions helps avoid issues in future.

As fast as the industry changes, events like CPhI make it clear these traditional concerns, along with issues such as maintaining data integrity and good manufacturing practice, continue to be key. It also suggest, though, that those companies that tackle them successfully, can look forward to the future with considerable confidence.