What is the MAPS Act? A Guide to the Mapping America’s Pharmaceutical Supply Act

In a muddle over MAPS? Read our brief introduction to the pharma supply chain visibility legislation currently making its way through the US Senate.

Pressure for government action to bolster the resilience of pharma supply chains has been building in the US for some time.

Among Joe Biden’s first actions as US President, a little more than a month after coming to power in January 2021, was Executive Order 14017. It aimed to “strengthen the resilience of America’s supply chains”.

Pharmaceuticals were a key focus.

That led to the 100-day supply chain review in June that year and, subsequently, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Essential Medicines Supply Chain and Manufacturing Resilience Assessment the following May.

Background – The Road to the First Pharma Supply Chain Bill

But while the executive continues to cajole the industry, other branches of government are pushing forward their plans. In the legislature, Michigan Senator Gary Peters has long taken an interest in pharma shortages and the supply chain issues that often underpin them.

In August 2019, as Ranking Member of the Senate Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee, Peters wrote to the FDA expressing concern over ongoing drug shortages – at the time, the highest in almost five years.

“Drug shortages are creating devastating health and economic consequences for patients, hospitals, and consumers. For patients, the impact on care is significant, as shortages cause delays when receiving emergency medications, undergoing medical procedures, and obtaining needed prescription drugs,” he warned.

That led to a report later in the year on “skyrocketing prescription drug prices and drug shortages”. It noted many of the now familiar issues around drug supply chain resilience, such as the reliance on China and India for active pharmaceutical ingredients. Rising prices and the shortages that often prompted them weren’t just a public health issue, Peters maintained, but a “national security crisis”.

By this year, and in the aftermath of the pandemic, the senator’s focus on supply chain vulnerabilities had intensified. A new report in March showed that “[D]rug shortages, as well as a lack of transparency into our pharmaceutical supply chains, present an ongoing national security risk and have made it harder for health care professionals to treat patients.”

The report found that between 2021 and 2022, new drug shortages increased by nearly 30 per cent. It also found that over 90 per cent of generic injectable drugs used to treat serious injuries or illnesses in the US relied on critical materials from China and India, and nearly 90 per cent of generic API manufacturing sites were located overseas.

Supply Chain Visibility as a Critical Issue

According to the report, tackling vulnerabilities was complicated by a lack of visibility in the supply chain.

“Neither the federal government nor industry has end-to-end visibility of the pharmaceutical supply chain – from the key starting materials, APIs, finished dosage and various other manufacturers that are ‘upstream’ – to the ‘downstream’ suppliers, which include purchasers and providers. This lack of transparency limits the federal government’s ability to proactively identify and address drug shortages,” the report notes.

It continues: “Although some generic drugs appear to have multiple and diverse drug suppliers, they in fact may rely on the same API source or manufacturer. As a result, the universe of actual suppliers for a particular drug may be much smaller than it appears, increasing the risk of shortage if that API source or manufacturer withdraws supply. The FDA is currently unable to assess the percentage of life-supporting and life-sustaining medications that have fewer than three manufacturers or rely on only one API supplier because the FDA does not have a list of life-supporting and life-sustaining drugs.”

Following the report’s release, Peters convened a full Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs Committee hearing to discuss its findings and recommendations.

“Drug shortages are not new. There are a number of factors that contribute to drug shortages, including economic drivers that lead to a lack of manufacturers willing to enter or remain in the market or invest in quality manufacturing systems, insufficient visibility into the entire supply chain for critical medications, and an overreliance on foreign and geographically concentrated sources for the materials needed to make these drugs,” Peters said at the opening of the hearing.

MAPS Introduced

All this led Peters and other senators to introduce two pieces of legislation to the Senate in July.

One, the Rolling Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient and Drug (RAPID) Reserve Act, introduced on July 26, 2023, aims to increase the supply of critical medications and mitigate “the national security threat posed by our nation’s overreliance on China for critical medications”.

It would do so by requiring the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to award contracts to “quality generic drug manufacturers” in the US or another OECD country to build and maintain reserves of critical drugs; oblige these contractors to keep sufficient reserves of key ingredients and finished drug products and production capacity to prevent potential shortages; and prioritise domestic producers for federal contracts.

The other, introduced just over a week before on July 18, with senators James Lankford and Mike Braun, was The Mapping America’s Pharmaceutical Supply (MAPS) Act – specifically aimed at boosting supply chain visibility as key to building resilience.

“As we saw firsthand during the COVID-19 pandemic, federal agencies did not have enough visibility into our reliance on foreign manufacturers and other chokepoints in the supply chain, limiting their ability to anticipate and respond to drug shortages and related challenges,” said Peters, introducing the bill. “This bipartisan legislation will provide the federal government with a more comprehensive understanding of the weaknesses in our pharmaceutical supply chains so we can take steps to address them and prevent future shortages.”

“This bill will shed light on the weaknesses in our pharmaceutical supply chains and allow us to make better informed decisions to address vulnerabilities in our drug supply chain,” added his cosponsor Senator Braun.

Mapping America’s Pharmaceutical Supply Act – Key Provisions

The bill consists of three key requirements:

- The HHS is to establish a federal database to map the origin of each drug, with the location of manufacturing facilities and associated inspections and risks, such as recalls and import alerts.

- It is to use this information to make data-driven decisions on supply chain threats and how to increase resiliency through strategic investments in domestic manufacturing.

- It must report to Congress on how it is doing so and any gaps in the remaining data.

It also requires the HSS to identify and regularly update a list of essential medicines, including both the drugs of their APIs.

These are defined as those likely to be required to respond to a public health emergency or chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat and those for which a shortage would pose a significant risk to the US health system or at-risk populations.

The bill's text makes clear how ambitious this is, stating that the intention is to map “the entire United States pharmaceutical supply chain, from inception to distribution”.

That includes the location of API and finished dosage forms of the essential medicines, including “the amount of such ingredients and finished dosage forms produced at each such establishment” and establishments involved in producing the key starting materials and excipients needed to produce the APIs.

It also requires the HSS to keep a database of regulatory actions, including with respect to labelling requirements, registration and listing information, recalls, inclusion on current and prior drug shortage lists and discontinuances of the medicines.

A Joint Effort – Pharma Industry Responsibilities Under MAPS

The need for private sector involvement is clearly stated in the bill’s text.

First, right at the outset, the proposed legislation clarifies that the supply chain mapping by the HSS is to be done in coordination with other relevant agencies, such as the Secretary of Defense and the Secretary of Homeland Security, “including through public-private partnerships”.

Second, the list of essential medicines is also to be drawn up (and maintained) “in coordination with the private sector”.

Moreover, where obligations on the industry are not explicitly set out in the text, they are heavily implied. Without massive industry input, it is impossible to see how the HSS could map the “entire” supply chain – from inception to distribution.

Should it try, its efforts are unlikely to be the last word: The bill provides that within 18 months of its enactment, the HSS must report on “gaps in data needed for full implementation”.

Next Steps for the MAPS Act

The Act has already received significant bipartisan support inside the Senate and from outside organisations, such as the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP), the American Society of Clinical Oncology, the American Hospital Association (AHA), United States Pharmacopeia (USP).

In a virtual summit in September on Drug Shortages co-hosted by USP, Peters reiterated his call to push through legislation: “We must urgently put these solutions in place to ensure that everyone can access the lifesaving medications that they need,” Peters told summit attendees.

While MAPS is not yet law, previous efforts will give supporters cause for optimism: In June, the President signed three bipartisan bills authored by Peters to bolster cybersecurity, including the Supply Chain Security Training Act.

His bill to strengthen US supply chains and domestic production capacity in relation to homeland security has also passed the committee stage.

It may be some time before MAPS is signed into law – or perhaps it will be usurped by legislation originating elsewhere. However, as we’ve said before, change is coming. The proposed legislation vindicates what we’ve long argued: That supply chain resilience begins with supply chain visibility.

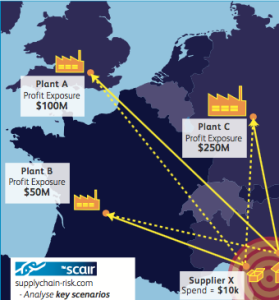

Pharmaceutical supply chain risk management software such as SCAIR® is specifically designed to address the issues highlighted by the Senate report that helped prompt the legislation, such as the concentration of risk through reliance on common API or manufacturing sources. As it noted, the “universe of actual suppliers for a particular drug may be much smaller than it appears”. SCAIR® is the x-ray vision that reveals these hidden vulnerabilities.

Likewise, the Act is right to focus on identifying critical drugs and points of vulnerability – not relying on the impossible task of identifying all the potential sources of disruption. Again, this is the approach we’ve long taken with SCAIR® – helping focus on impacts, not causes.

We’ve long believed this is the best route to supply chain resilience. Increasingly, it seems likely to be the approach governments will insist the industry takes to ensure the supply of critical drugs is maintained.

Acting now, using tools such as SCAIR® to gain visibility – and sharing it as required – will enable pharma businesses to ensure the relevant authorities see them as allies rather than obstacles in that effort.