Climate Change, Supply Chains and Compliance

Regulatory requirements dictate that large companies carefully evaluate their supply chains’ exposure to risks from extreme weather. Done properly, however, the exercise can bring far wider benefits.

Climate continues to cost the earth – in all senses. According to insurance broker Aon, insured losses from natural catastrophes, like hurricanes and floods, reached $118 billion last year. The losses, across almost 400 events, were more than a fifth above the average for the century. There were also 37 events that saw losses of $1bn or more – a new, dismal record.

The costliest event of the year was still earthquakes, with those in Turkey and Syria seeing insurers pay out $5.7 billion. However, New Zealand, Italy, Greece, Slovenia and Croatia all saw the most expensive weather-related insurance events on record.

And that’s just insured losses.

Most damage is not insured, and the actual losses to individuals and businesses are many times higher. The economic loss of the Turkey and Syria earthquakes alone is estimated at $92bn. The death toll was 95,000 – the highest in more than a decade.

Again, that is driven not just by 64,000 fatalities from earthquakes but 16,500 deaths from heatwaves around the globe.

Last year was the hottest on record.

Just the Start: Climate Losses will Mount, Fear Insurers

Such losses are changing the very way insurers think about risk.

Traditionally, the insurance industry has distinguished between the big-ticket primary perils, such as tropical cyclones, earthquakes, and European windstorms, which are relatively infrequent but cause massive losses and secondary perils.

More frequent but traditionally considered more manageable because of the smaller losses, are natural catastrophes like thunderstorms, floods and wildfires.

Climate change is altering insurers’ perspective.

Aon’s report showed that these “secondary” perils have caused significantly more losses to insurers than primary perils over the last decade due to their increased frequency and severity. In 2023, primary losses were a distant second, accounting for only 14 percent of global losses.

As the chief climate scientist of Munich Re (the biggest “reinsurer” that provides cover for insurers against really large losses) recently told the Financial Times: “We no longer can call such events secondary. They have reached in the aggregate the order of magnitude of a major hurricane, or tropical cyclone, or winter storm.”

As the FT article makes clear, this is not just a problem for insurers but for businesses and individuals, too, as underwriters decide there are risks they just do not want to take. We face the prospect of certain locations becoming uninsurable.

Moreover, it is a problem that may only get worse. Last year, Lloyd’s of London warned insurers that the full impact of climate change had yet to be fully felt when it comes to claims. According to the FT, again, it is urging insurers to be proactive in addressing the risk.

“By the time we can definitely see the impact in claims, it will be too late,” Lloyd’s director of portfolio risk management told a private meeting.

Pharma Supply Chains: TCFD and Beyond

Since the pharma sector is no stranger to the risks of weather impacting its supply chains, all this provides one good reason for it to take climate change seriously.

Another is that it increasingly does not have a choice.

It’s not just insurers who have become increasingly aware of the financial risks posed by more frequent extreme weather events.

Governments and regulators, too, have recognised the growing danger and the possibility that it could pose systemic risks to financial stability. States have, therefore, been putting ever greater pressure on businesses to identify, quantify and address those risks.

As we’ve discussed before, that was led by the Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures in the UK. It introduced the requirement for big businesses (to apply to all businesses by 2025) to report the impact of climate change on their supply chains. It was disbanded last Summer – but only to be replaced by the IFRS Foundation, which was tasked with taking forward its work by the Financial Stability Board.

The IFRS has already clarified that the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB) standards launched in June 2023, fully incorporate the TCFD requirements.

You can read our earlier blog for a fuller explanation of the requirements and why tools like our supply chain risk assessment SCAIR® are so valuable in helping businesses comply.

However, here, I’ll concentrate on just two aspects, which we have highlighted in our recent video on TCFD, climate change and quantifying risk.

Bringing Value at Risk into the Real World

The first is that SCAIR® doesn’t just provide a tool and framework to accelerate the process, enabling organisations to comply more efficiently. It also helps avoid common pitfalls and ensures the exercise has real organisational value.

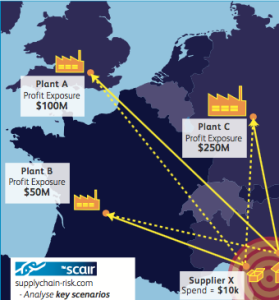

For example, SCAIR® helps identify risks to products and focuses on those with the highest revenues. This can quickly help companies reach a robust figure for the value at risk at each location. Crucially, though, it doesn’t just estimate the potential losses in terms of pure gross profits.

In the event of a catastrophic climate-related event, no business will simply watch as their primary sources for profitable products vanish.

They will use their existing stocks, inventories and reserves and quickly seek to source other suppliers and additional production capacity.

SCAIR® accounts for that and seeks to provide a real-world value at risk – not simply a box-ticking exercise for regulators but a genuinely helpful and crucial piece of business intelligence.

Climate Change Supply Chain Location Mapping

That grounding in the real world needs to be replicated when evaluating the risks of climate change.

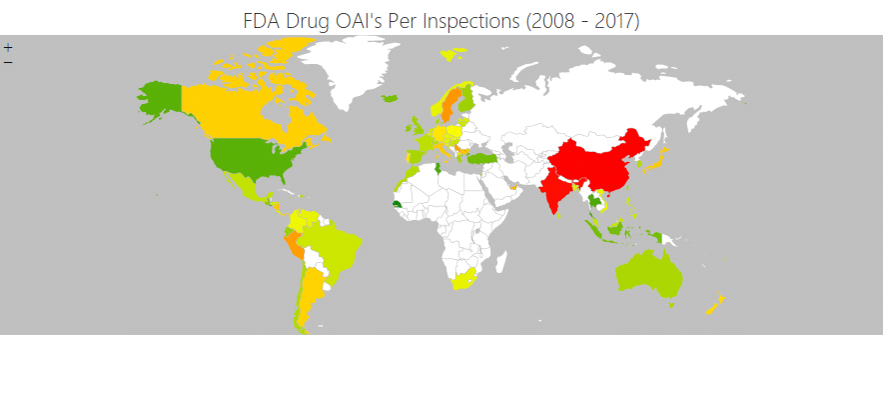

Existing risk assessment methods suffer significant faults. In many cases, they are not location-specific, substituting an evaluation of the specific risk of a site with broad, regional risk evaluations.

Even worse, existing solutions are usually backward-looking. They assess the risk to a location by reference to the past without accounting for the impact of climate change in worsening extreme weather.

In a sense, this ignores the entire purpose of the exercise.

SCAIR® addresses this drawback by interfacing with Location Risk Intelligence, reinsurer Munich Re’s solution for assessing physical risks from natural hazards (previously called NATHAN) and climate change.

Munich Re’s Risk Management Partners division uses the world’s most comprehensive disaster database and sophisticated modelling to provide robust, location-specific climate change predictions.

Again, this ensures that it is not simply a compliance issue but an exercise with real value. The intelligence from SCAIR® and Location Risk Intelligence enables businesses to focus on locations at the highest risk from further natural catastrophes due to climate change.

A Boon for Business Continuity

Indeed, this is the real value of the exercise beyond compliance.

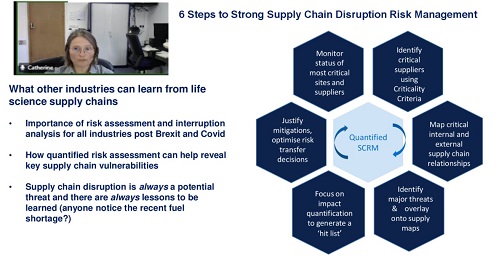

Identifying vulnerabilities in the supply chain and developing robust intelligence for both values at risk and the risk itself enables businesses to anticipate and address their business interruption exposure at critical nodes.

That might mean diversifying supplies to build increased resilience into the supply chain. It might mean putting in place extra measures, such as increased stocks or other ways to mitigate losses. Credible figures for the value that could be lost at a site can be used to justify investments to protect against them.

If interruptions to a site prove unavoidable, SCAIR® gives businesses the tools to lessen the impact.

It can enable businesses to assess the impact of catastrophic events more rapidly and respond more effectively than those without such planning, for example.

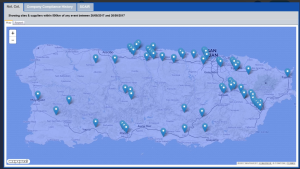

Read our case study on how it helped a large pharmaceutical manufacturer quickly implement continuity plans to lessen the impact of a Puerto Rican hurricane.

Finally, if all else fails, a better understanding of exposures and the value at risk in each location provides a basis for calculating the insurance required for the residual risks that cannot be addressed.

It provides businesses with the insights needed to purchase an appropriate level of business interruption cover and, perhaps, to make their case to secure affordable premiums in a tough market going forward.