More than Covid: Lessons for Supply Chain Resilience from 2020

Hard Truths from a Pandemic

Pharma and others in the life sciences shouldn’t let the lessons learned from the crisis go to waste. As we emerge on the other side, now is the time for a strategic review of supply chain vulnerabilities. Intersys Risk Director Catherine Geyman, takes stock of the situation.

It’s been an unprecedented year for life sciences. The pressure on both supply and demand as a result of the pandemic was unparalleled in modern times.

As Peter Ballard, Chair of the British Generic Manufacturers Association (BGMA) put it in the organisation’s review: “At the peak of the first wave in the UK, the pandemic derailed all sense of normality. It thrust healthcare and its supply chains into the forefront of public consciousness as the NHS staff struggled to keep pace with patient demand with the resultant knock-on effect to the medical supply chain.”

It was the perfect storm: huge increases in demand which could not have been planned for by the pre-covid supply base; and massive disruption to supply chains as a result of staff absences and government constraints.

In the UK, generic medicines make up more than three-quarters of all prescribed drugs. According to the BGMA, which represents UK-based generics manufacturers and suppliers, demand for some drugs was five to ten times higher than usual. At the same time, an export ban on active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from India – accounting for about half of APIs used by British generic medicines – came in, in March. BGMA members reported a 24% reduction in supply from the country. Companies also saw a decline of over a fifth in finished products from India.

And it wasn’t just the UK, of course. We’ve looked at shortages in the US earlier in the year. There, our analysis showed that, with a few exceptions, shortages were mainly demand-driven, as the virus saw a clamour to get hold of certain anti-virals, anaesthetics and sedatives. Companies reporting new drug shortages in the US rose from 19 in January to 71 by April. Nor was it just a life sciences issues, even if the industry was hard hit. As the Harvard Business Review recently noted, “The supply shock that started in China in February and the demand shock that followed as the global economy shut down exposed vulnerabilities in the production strategies and supply chains of firms just about everywhere.”

With vaccines developed, this might be the beginning of the end for Covid. For those in pharma and the broader life sciences, though, it should just be the beginning of a strategic review of the impacts on their supply chains and what we can do differently in future to minimise disruption.

To quote the BGMA again: “COVID-19 has presented unprecedented challenges, but it would be unforgivable not to learn from those and apply that experience to the future.”

It’s in this spirit that I recently held a webinar on Understanding Risk in Pharmaceutical Supply Chains.

Learning the lessons?

As that webinar underlines, there are two reasons why we need to take this opportunity to look back before going forward. First, because it might be unwise even now to think the challenges the virus presents are at an end. The vaccine roll out will take time in the UK and elsewhere; the Pfizer supply chains themselves are already facing disruptions due to out of specification raw materials. Many still fear a third wave of the virus after Christmas. In other words, there are still plenty of opportunities to surprise and disrupt supply chains.

Even if we have managed to put this crisis behind us, the pandemic has shown what is possible. It could happen again. Businesses must prepare for the next crisis, not the last one.

It doesn’t take a worldwide catastrophe to cause supply chain disruptions, however. Well before this spring, drug shortages were again making themselves felt.

Unsurprisingly, there are several reasons for shortages. In some cases, it is other significant events; it’s worth remembering that before Covid the critical concern for the UK was Brexit, something of which we may shortly be reminded (particularly since buffer stocks put in place for Brexit have been used during the pandemic). US supply lines, meanwhile, have been repeatedly hit in recent years by hurricane activity in the likes of Puerto Rico.

But in addition to these significant disruptions to supply, there are a whole host of other, lower-impact, higher frequency events and risks that, if not managed, can escalate over time and eventually cause supply interruptions. They include failures to meet on-time, in-full (OTIF) targets as a result of delivery delays or batches not released; process variability, quality deviations or unreliable manufacturing or API plants; lower profile supply chain disruptions – the result of critical material shortages, facility damage or transit failures; and, finally, product shortages as a result of recalls or other regulatory intervention.

The majority of these events normally do not reach public scrutiny as they are usually handled and mitigated by having safety stock in place. If problems persist, however, that reserve can be eroded and eventually exhausted, resulting in drug shortages.

The critical point is that Covid did not always cause the weaknesses we’ve seen in supply chains. It often just revealed them.

Long-term fragility

To understand why, and how drug shortages have re-emerged to challenge the industry, it’s necessary to recognise the long-term trends that have increased companies’ exposure to supply chain disruptions. Three related themes are essential.

The first is the accountant’s drive to make supply chains more efficient that has seen businesses cut back on stock and redeploy backup facilities to productive use. Mergers and acquisitions resulting from the same push for efficiency, meanwhile, have reduced the number of suppliers for crucial APIs, eliminating redundancy in the supply chain. This a relatively simple point: By reducing both the range of alternative providers and internal production capability and stock levels, we’ve inevitably reduced the resilience of supply.

The second is again the result of the determination to cut costs: Outsourcing to countries with lower labour costs, which has focussed industry dependencies on fewer API or contract manufacturers. As noted above, this has resulted in businesses heavily dependent on India, and to a lesser extent China for APIs. Disruption in the event of an export ban or similar block on supplies will almost inevitably be felt downstream. Indeed, this issue rapidly came to the fore right from the start of the pandemic.

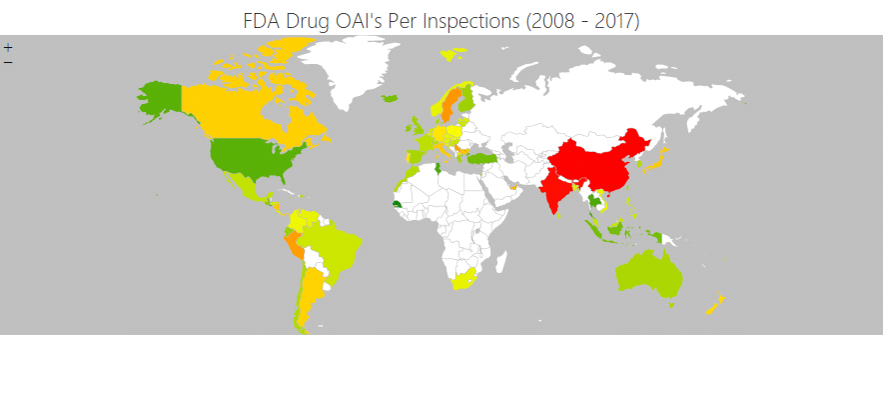

The industry’s decision to shift API production to Asia has also increased drug supplies’ reliance on jurisdictions with less mature regulatory systems and, hence, potentially lower standards. There is no escaping that the regulatory track record of China and India is demonstrably inferior to that of the UK, Europe or the US.

In the image below, the colour coding shows the frequency of OAIs (Official Action Indicated notices) issued to facilities by the FDA as a percentage of the number of inspections conducted. In the US and Europe, the likelihood of an OAI was usually below five or six per cent (green and light green). In China and India, the rate was more than eight per cent (red).

Source: research by Intersys Ltd as part of the ReMediES project.

That’s a particular issue because while manufacturing of APIs has moved to jurisdictions with arguably lower standards, regulatory requirements have, if anything, moved the other way.

In practice, this can result in disruptions to the supply chain in one of two ways. First, where a compliance failure occurs, the OAI often results in prolonged plant shutdowns for remediation. Second, remediations that result in major changes or new suppliers will take time to be approved by the regulators.

It’s an irony that the regulatory measures in place to protect patients, can count against the patient if something goes wrong in the supply chain and extensive regulatory re-approval is required for the solution to put it right. This is far from being a theoretical risk. An FDA report in 2019 showed that of 163 drugs that went into shortage from 2013 – 2017, 62% followed supply disruption associated with manufacturing or product quality problems. Moreover, there is an interplay between regulatory risks and the other vulnerabilities from long-term trends touched on above. As a result, certain types of drugs are particularly vulnerable to supply chain interruptions.

This is confirmed by both the FDA report and a study led by Intersys with the Institute for Manufacturing at the University of Cambridge, part of a cross-industry collaboration project called ReMediES, which revealed that 69% of product shortages in 2018 followed OAIs issued to the company reporting the shortage. Both studies showed that the drugs most likely to be in shortage were generic injectables, which require rigorous manufacturing processes but do not provide much profit margin as a result of competition. (A BMGA study of 40 originator products to come off patent since 2014, shows sale prices fell by an average of 89%.) Older drugs with a median time since first approval of almost 35 years are also more to be in shortage.

Price competition for older generics makes investment in robust quality management systems difficult. Moreover, in the event of an interruption that causes the drug to become scarce, low prices and regulatory hurdles discourage new market entrants from correcting the situation.

Seeing is believing

There’s one final factor that explains the rising disruption to supply chains, and it’s an important one: The increasingly global nature of life sciences businesses and the complexity of their supply chains has decreased visibility and oversight of them. The result is that both the underlying vulnerabilities and interruptions to supply chains are more difficult to detect and address.

As my presentation outlined, the life sciences supply chain takes in a broad range of other industries. These also vary considerably, depending on whether we consider biologics, traditional pharmaceuticals or medical devices. These bring a range of second-tier suppliers and contract manufacturers into consideration. As a result, life sciences businesses can find themselves exposed to a range of risks to livestock, chemicals or engineered components businesses.

Trying to predict the full range of possible events that could impact these suppliers is arguably impossible. What businesses can do, however, is to identify the most critical suppliers, and determine the value at risk for the critical dependencies of key products.

Understanding where these vulnerabilities lie enables the business to focus on these so that impacts on them are identified and responded to more quickly. Quantifying the value at risk, meanwhile, allows proper evaluation of risk mitigation options through a cost-benefit analysis.

Crucially, neither require you to anticipate what event might cause the disruption – only the vulnerabilities and value at risk. That’s important because it’s what the last year has really shown us: That we need to be ready for anything.

For more on these issues and particularly how SCAIR can help with identifying mapping, quantifying and addressing critical exposures, watch the webinar for free here.

Catherine Geyman, Director, Intersys Risk Ltd